“Automation and cybernation can play an essential role in smoothing the transition to the new society… The computer can be used to direct a network of global thermostats to pattern life in ways that will optimize human awareness. Already, it’s technologically feasible to employ the computer to program societies in beneficial ways… There’s nothing at all difficult about putting computers in the position where they will be able to conduct carefully orchestrated programing of the sensory life of whole populations. I know it sounds rather science fictional, but if you understood cybernetics you’d realize we could do it today… whole cultures could now be programed in order to improve and stabilize their emotional climate, just as we are beginning to learn how to maintain equilibrium among the world’s competing economies.”

INTERVIEWER: “How does such environmental programing, however enlightened in intent, differ from Pavlovian brainwashing?”

MCLUHAN: “Your question reflects the usual panic of people confronted with unexplored technologies. I’m not saying such panic isn’t justified, or that such environmental programing couldn’t be brainwashing, or far worse—merely that such reactions are useless and distracting. Though I think the programing of societies could actually be conducted quite constructively and humanistically, I don’t want to be in the position of a Hiroshima physicist extolling the potential of nuclear energy in the first days of August 1945. But an understanding of media’s effects constitutes a civil defense against media fallout.

“The alarm of so many people, however, at the prospect of corporate programing’s creation of a complete service environment on this planet is rather like fearing that a municipal lighting system will deprive the individual of the right to adjust each light to his own favorite level of intensity. Computer technology can—and doubtless will—program entire environments to fulfill the social needs and sensory preferences of communities and nations. The content of that programing, however, depends on the nature of future societies—but that is in our own hands.”

— The Playboy Interview: Marshall McLuhan, March 1969

I have only ever earned a very minor reputation for myself as an academic. But it’s one I’ve come to treasure all the same.

This little notoriety stems from my only published research , a slim nine pages that first appeared in the tenth volume of Young Scholars in Writing. That volume was published by a team based out of the University of Missouri-Kansas City, but the journal had been founded at Penn State Berks a decade prior as “the first international undergraduate research journal in rhetoric and writing studies”. It remains in print today, though now based at York College of Pennsylvania.

In the years since then, Semantic Scholar informs me that my paper has been cited in five other, peer-reviewed works. Google Scholar has the figure at twelve – theirs includes thesis papers and the like – with the earliest dating back to 2015 and the most recent having been earlier this year. Also (it is at this point I must confess to sometimes egosurfing, and thus being an insufferable human being), the article has appeared on “required readings” lists of post-secondary courses on a range of subjects, on campuses across no fewer than four continents. I am perhaps most proud of the ‘Seminar on History of Western Legal Thought‘ where my work was discussed several years ago by students of the College of Law at the National Chengchi University in Taiwan.

There is a non-insignificant part of me that suspects this (relative) success came down mainly to what you might call “academic search engine optimisation“. What I mean is that I had chosen a rather catchy (and in hindsight, keyword-dense) title for my paper – Social Media and the ‘Perpetual Project’ of Ethos Construction – and that great pains were taken through the editing process to ensure that its premise would be obvious from the abstract forwards (that premise essentially being “hey, the ways that people communicate through emergent ‘social media’ platforms, right now, are sort of interesting to think about, aren’t they?”).

This all had the virtue of making my article something of an ideal source text, of the kind that other researchers might paraphrase somewhere in the preamble of their own works, gesturing vaguely towards my own as if to say “See? We can talk about these things!”, before proceeding to discuss whichever far more interesting things they had meant to from the outset. That, to my mind, is the best theory for making sense of the sheer breadth and depth of fine scholarship in which my own thoughts and work now figure, to greater and lesser extents. Not that I am complaining – far from it! With rare exception, and inasmuch as I’m able, I feel both grateful and glad that I could help.

Pulling The Pin Out

Don’t let my hairline fool you: I just turned thirty-four this year. That puts twelve (or so) years between myself, the author of the words you are reading, and that promising young undergrad who self-described as keeping “fairly lax control over his online privacy”. What, you might ask, ever came of him?

Well, at some point in the past year, I seem to have changed the date-of-birth on my Facebook account to January 1st, 1977. I don’t recall the when or the why of it, but it seems like something I would do. The only trouble of it was when a relative took the time to wish me a happy birthday, several weeks early, and then somebody else did it, and by that point it’s far too awkward to go about correcting anyone in specific, because why even is your birthday set wrong?, so you just don’t say anything, and then a week goes by, and you think “hold on, if I change it back now and maybe write a post to explain, will people think I’m fishing for happy birthdays?”, and then another week goes by, and then it’s autumn…

In short, he tripped and fell – like so many promising young minds before and since – into a career in advertising, and a decade spent at that vocation has rendered him helplessly paranoiac. That is not his term for it, mind you: he prefers “distrustful”, since “paranoia” suggests a degree of unreasonableness, which he roundly disputes. Currently, he is passing for a Gen-X Capricorn on his socials, and will continue doing so into the foreseeable future.

It worked, by the way! Now all the ads in my feeds are about insurance and trucks.

Meanwhile, in March of this year, his alma mater suffered a catastrophic data-breach, exposing personal and financial records about just about every student enrolled there in the past five years, and every person employed there over the past two decades. A months-long investigation, commissioned after the fact, would ultimately conclude that the data breach had been somehow even rather worse than that – a finding the University would share with those affected by quietly dumping the news on a Thursday afternoon in August.

(It is difficult to overstate the severity, the scale, or the seriousness of the University of Winnipeg’s failures in this regard; the most recent lists of “populations likely impacted” make for grim reading. Administrators there would appear to have embraced a Creosotian approach to data governance and security, and just mixed everything together in one big bucket. Some of the records compromised in the March cyber-attack date back to 1987, two full decades before most of the University’s incoming first-years were even born. Some of the data is acutely sensitive, including passport details in some cases, and just about every scrap of “personal health information” collected and catalogued, for any administrative purpose, by that institution. The true “costs” of the breach – in terms of harms, both real and potential – are incalculable, but suffice it to say that it is now an overt and irrevocable security risk to identify, or to be identified, as an alumnus of the University of Winnipeg, or to have been affiliated in any way with that institution at any time in living memory. Wherever possible, it should be avoided. Put that in the recruitment brochures!)

Owing to the nature of his work, he was already bleakly aware upon hearing the news of this breach that under Manitoba’s feckless and archaic privacy laws (which apply, in lieu of PIPEDA, to the so-called “MUSH” sector: Municipalities, Universities, Schools and Hospitals), those university administrators who were (and are) responsible can only ever bear up to $50,000 in individual liability, regardless of the scale or impacts of the breach. By contrast, the University of Winnipeg would now be liable for tens of millions of dollars in potential civil penalties, were that school held to the same data-protection standards as its European counterparts… or its counterparts in Québec, for that matter.

This lone fact, moreso than any other, will explain the conditions which led to the runaway success of the March 2024 cyber-attack on the University of Winnipeg. It also explains why, despite my better efforts and against my better wishes, the words of my contributor bio for Young Scholars in Writing shall remain true forever: additional details about the author can likely be found online, for those who are curious.

Occupational hazards, perhaps. But it is only thanks to these (and other) lived experiences, and the convictions these have engendered in me, that I feel prepared – now and at long last – to address a subject that I myself could only gesture vaguely in the direction of, all those years ago, with this brief and desultory footnote:

It should be pointed out that while media theorists (such as Marshall McLuhan or, more recently, Ben McCorkle) have argued that the form of media necessarily affects the communication which takes place through it, and certainly the same case could be made concerning social media, a larger discussion of how social media platforms themselves act as another “author” by influencing the communication of users is beyond the scope of this essay.

Looking back on it now, this latest series of blog-posts – what began as my unabashed love letter to the 1973 Massey Lectures – reads a lot like my own good-faith best effort to return to, and grapple with, this very same concept:

- In Part I, I issued a sort of “state of the industry” when it comes to marketing via the modern, commercial Internet (TL;DR: it’s a disastrophe!).

- In Part II, I listed off five key “pain points” of today’s ads-supported digital economy (tackling ad fraud; respecting user consent; improving data quality; and a glaring lack of regulation and/or oversight in both machine-learning and “generative AI” systems now deployed at societary scale). These “pain points” have remained nearly as constant and unchanging over the course of my working life as has the list of major publishers, platforms and firms that have come to dominate this global “attention economy”.

- In Part III, I relayed a few of the more radical aspects of Stafford Beer’s cybernetics, and stressed his arguments for the intrinsically finite nature of the brain – we might restate these by saying “folks can only ever be, or get to being, so smart“. Then, with the help of some local crime stats that were handy, I introduced “control charts” (and “statistical process control” more broadly) as a tool that one might use to organise the noisy, complex data collected from (and about) real-world processes into tangible signals, of a kind which these finite brains of ours find useful when seeking to predict the future, based on what has happened before.

Having now addressed each of the above points with due attention and care, it has now come time for me to attempt an enquiry into the causes of all these problems I’ve described. My hope is to form some decent theory as to their origins, and why they persist, and what might yet be done about them. And to save you from any suspense, I feel like I have, and that this series of posts turns out all the better for it. But if you’re really pressed for time, then feel free to just scroll down to the bottom of this post, and turn your screen upside down to read the answer.

“Exactly Like This With… Certain Susceptibilities…”

Towards the end of Part III, I broke off a quotation from Designing Freedom, just after Stafford Beer exhorts his audience “to remove the control of science and technology from those who alone can finance its development, and to vest its control in the people”. For our purposes, I felt that this would be a better place (and time) for what he had to say next. Here is the bit I left out:

How realistic can this solution possibly be? After all, people who have power simply never hand it over to others; moreover, in this case vast sums of money are involved. I reply that the solution is realistic in a democratic society to the extent that the demand to redesign societary institutions is made articulate. The process can begin by debunking the mystery surrounding scientific work. It would make a very good basic postulate for the ordinary citizen to say something like this to himself, and to discuss it with others:

“For the first time in the history of man science can do whatever can be exactly specified. Then, also for the first time, we do not have to be scientists to understand what can be done. It follows that we are no longer at the mercy of a technocracy which alone can tell us what to do, Our job is to start specifying.”

For this new channels are needed. But of course they could be set up. What is television for? Is it really a graveyard for dead movies; or animated wallpaper for stopping the processes of thought? What is the computer for? Is it really a machine for making silly mistakes at incredible expense? What will be done with cybernetics, the science of effective organization? Should we all stand by complaining, and wait for someone malevolent to take it over and enslave us? An electronic mafia lurks around that corner. These things are all instruments waiting to be used in creating a new and free society. It is time to use them.

— Stafford Beer, Designing Freedom, p. 29 [emphasis mine]

At no other point does Beer elaborate directly on this “electronic mafia”, but in this later passage — and especially in his lecture notes — its correspondence with what Shoshana Zuboff calls “surveillance capitalism“, or what Cory Doctorow has more recently dubbed “the enshitternet“, becomes inescapable:

Which brings me to the second example, namely publishing. If education begins the process of constraining our cerebral variety, publishing (whether on paper or by radio waves) continues it for ever. The editorial decision is the biggest variety attenuator that our culture knows. Then the cybernetic answer is to turn over the editorial function to the individual, which may be done by a combination of computer controlled search procedures of recorded information made accessible by telecommunications. Cable television has all the potential answers because it can command eighty channels. This offers enough capacity to circulate the requisite variety for an entirely personalized educational system, in which the subscriber would be in absolute command of his own development.

Well, we are frightened of this projection too. Someone may get inside the works, we say, and start conditioning us. Maybe we should have eighty alternative standard channels, thereby “restoring choice to the people”. Here is my third and last bit of mathematics: eighty times nothing is nothing. Meanwhile, we allow publishers to file away electronically masses of information about ourselves — who we are, what are our interests — and to tie that in with mail order schemes, credit systems, and advertising campaigns that line us all up like a row of ducks to be picked off in the interests of conspicuous consumption. I know which prospect frightens me the more.

— Stafford Beer, Designing Freedom, p. 31 [emphasis mine]

Run the Numbers

The more I thought about it, the more compelling “electronic mafia” became to me as a metaphor for the commercial Internet which you and I know and experience today. On a surface level, the phrase invites comparisons between the strategies and tactics of “Big Tech” and those of organised gangsters; experience has long since impressed on me their moral equivalence, but others could arrive at a similar conclusion, by way of other arguments.

The metaphor really started to click for me after I had done some reading up on how real, lower-case-M “mafias” have operated in cities across North America (and beyond) over much of the past two centuries. Like many people, my basic concept of “the mob” owes more to the films of Brian De Palma and Martin Scorsese than it does to any real-world gangsters. Small wonder, then, that our shared cultural stereotype of “the mafia” tends to focus on that enterprise’s more dramatic and/or cinematic aspects: the sex trade, the drug trade, the guns and the gambling, the betrayal and envy and greed. But in order to appreciate “electronic mafia” as metaphor to its fullest extent, one must appreciate that an essential revenue stream of actual, historical mafias, over long spans of time, has been simply this: the local mob would control the local “numbers game“.

I won’t attempt to give a history of “policy rackets” here, nor of the “numbers rackets” which emerged later on, since this would end up being more-or-less a full history of the industrialisation and urbanisation of North America. The main thing to know is that “policy” and “numbers” were (and are) both fairly simple unregulated forms of lottery. More charitably, one could describe them as “self-regulated” lotteries, although “mob-run” would be equally valid. Policy games often looked similar to the modern “Powerball” lotteries held in and by most U.S. states, whereas “numbers games” involve betting on the outcome of some “sufficiently random” number, typically three digits in length.

There are two key design principles – and there might be more, but I stopped myself at two – which distinguish these games from other and earlier forms of illicit gambling. The first principle is universal access: in the crowded cities, a bookmaker was never far away, and many were even willing to accept wagers of as little as one penny on such games. If you didn’t have the penny to wager today, then a friendly bookie might even loan one to you (on very reasonable credit terms, I’m sure). And, with the rise of new mass communication technologies such as radio and wood-pulp newsprint, plausibly “fair” games of chance were no longer constrained to the gambling halls. If you were alive to check the papers tomorrow, then you too could play along.

The second design principle relates to what economists call “network effects“. Obviously it would be uneconomical to run such a complex lottery, with such low costs of entry, for the entertainment of a mere handful of bettors. But as the total number of bettors grows to hundreds, or thousands, or tens of thousands, then even the meager wagers placed by most can still add up to a rich sum. Let’s suppose that your local bookie offers 600:1 odds (as was common, apparently) on the outcome of tomorrow’s “number”, so that a correct wager of just one penny would net you six dollars, and a correct wager of five dollars would pay out $3,000. This seems like an undeniably attractive offer, to a certain kind of gambler (with… certain susceptibilities…), but it is even more appealing to the bookie, since they understand that the odds of any one bettor’s wager ever being correct are 1000:1. In practical terms, this means that a winner (or winners) might have to paid out on occasion, and that these payouts might even need to be big from time to time… but the long-term trend overwhelmingly favours “the house”, especially when a maximum bet is enforced. And in the meanwhile, if some bettors get the idea that they ought to be placing two bets, thus raising their odds of success to 500:1 (but also ensuring that at least one wager will be lost), then any friendly bookie would happily “take that action”.

The “numbers game” flourished throughout much of the post-bellum United States, proving especially popular in some of the poorest and most blighted neighborhoods of America’s largest urban-industrial centres. This highly profitable era of mob-sanctioned “numbers running” would only end once total legal prohibition (which had existed in the United States at the time) against such lotteries was relaxed, and state governments began running their own state-sanctioned lotteries to compete directly with the mob games. This is still a relatively novel development on the timeline: for context, as of 1895 there were zero legally-operating lotteries in the United States; forty years later, in 1934, the first modern U.S. state lottery was established in Puerto Rico; and thirty years after that, New Hampshire’s state lottery became the second in 1964. Meanwhile, in Canada, the Criminal Code effectively outlawed most forms of lottery between 1892 (the year it was first enacted) and 1970, when the P.E. (read: O.G.) Trudeau Liberals passed sweeping changes to the Code, enabling provinces and territories to license and regulate gambling in their own jurisdictions. The growing popularity – and ease – of offering betting odds on professional sports has also been a key factor in the gradual decline of “the numbers game”.

You Wanamaker Bet?

There are two conclusions I feel that we can draw from this history. The first: that the very human needs for entertainment and play do not seem to index to one’s income. The second: that there is some profit to be had in offering long, bad odds to desperate, irrational people. Yes, really. Who knew?

John Wanamaker, the nineteenth-century American retail tycoon remembered for inventing the “price tag”, the “money-back guarantee”, and for hiring the world’s first full-time advertising copywriter, is also credited with that famous and oft-repeated quip that “half the money I spend on advertising is wasted; the trouble is, I don’t know which half”. And the simple, awkward truth at the heart of modern digital marketing is still very much the same as in Wanamaker’s day — that advertising is a speculative investment. It is a gamble, and often not a smart one.

Advertisers seek to prompt some action or behaviour on the part of some audience, and so they invest in crafting and delivering some message, in hopes of inspiring and/or effecting this. Once the advertiser’s media has been “placed” by the publisher, then hopefully some people will see it, and hopefully some of the people who see it will take note of it, and hopefully some of those people who took note of it will then act and/or behave in the ways the advertiser hoped they would. That is still very much the fundamental value proposition, and it would arguably have been much clearer in a pre-digital mass media culture, since there were only so many channels through which a mass audience might economically be reached.

The birth of the commercial Internet heralded a revolution in publishing because it made theoretically feasible, for the first time, for “paid media” such as ads could be transacted on a basis of performance. The idea was that if a publisher “placed” media on behalf of an advertiser, but that media was not subsequently viewed and/or engaged with by their target audience, then the advertiser was not obliged to pay. Think of “pay per click” pricing for ad placements in the Google Search results page, or the push to make “viewability” a foundational metric in online display advertising. Again, we find an undeniably attractive offer taking shape, to a certain kind of advertiser. With certain susceptibilities.

The current (and ongoing) revolution in publishing is a counter-revolution of sorts. It kicked off in earnest eight years ago, and largely recognises that “the juice” of our modern, ads-supported Internet has very much not been worth “the squeeze”. There is now a seeming broad consensus that the technologies we depend on to support marketing use-cases would ideally not enable such harms as intimate partner stalking, or racial discrimination in access to housing, or other systemic human rights abuses. At the same time, digital marketers are realising — as we contemplate a “post-cookie” future, without deterministic signals telling us “this user did this thing at this time” — that even some of our most basic “performance marketing” use-cases, like frequency-capping or even determining the number of users who were exposed to an ad, prove fiendishly difficult in a digital context.

As I type these words, twenty U.S. states have already enacted comprehensive new data privacy laws since 2018 (when the GDPR went into effect all across the European Union). No fewer than seven of those state laws are already in legal force, with at least four state legislatures actively debating similar bills. Tens of millions of Americans enjoy far greater choice, and greater legal recourse, over whether and how their personal data gets used by the digital services they interact with today. It is a stark break from the “don’t-worry-darling” attitude which has pervaded much of the commercial Web’s history.

On the “buy-side” of the digital advertising industry, these and other changes have cumulatively made both identity resolution (ie. “who did we reach?”) and conversion attribution (ie. “what happened next?”) much, much more difficult. From a certain perspective, which I do not share, you could say they’ve both gotten much, much worse. With each passing day, the trust that marketing managers had once placed in their various reporting dashboards, their long-established KPIs, is being blasted all to pieces by these broader, structural shifts in the commercial Internet. That part’s the good news.

The bad news is that digital marketers already do — and increasingly will — find themselves spending inordinate time poring over mostly “sampled”, “modeled”, and “estimated” data as feedback on their work, hoping against hope to gain some insight or clarity from these, and more often finding none. But that is not the worst of it: what is worse is that most marketers have (and will) simply continue on as they always have — still making choices and forming conclusions as before, but now from a place of firm non-understanding of the data they collect and consume.

Recall what I had said earlier, in Part I: fraud is not just a strategy of marketers, but I believe it is the most prevalent strategy in this line of work. So for many organisations, the difference will hardly be noticed.

The House Always Wins

On the “sell-side” of the equation, an emerging and more privacy-conscious Web presents direct and existential threats — but also opportunities — for many powerful corporate interests (Meta and Google being chief among them, but also Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, ByteDance, etc.), who’ve built stable and highly lucrative business models off of collecting, processing and selling the personal data of their users and/or the inferences drawn from it. We should probably stop to ask, then, how the giants of Big Tech have fared through these crises?

The answer, as it turns out, is “fine, thanks”: Meta just posted its best Q2 ever, with advertising revenues up by 22 per cent year-over-year. Google’s parent company, Alphabet, had its best-ever fiscal quarter in Q4 2023, when it smashed the previous quarterly ad-sales record by nearly $10 billion. With those kinds of numbers, we should probably stop to ask one further question: what gives?

Both Google and Meta have long offered a “free-tier” ad-buying surface (“Google Ads” and “Meta Ads Manager”, respectively), which most small to mid-sized advertisers, and even some enterprise-scale ones, are obliged to use when purchasing and placing media on any of the platforms they own. Between the two, that list includes: Google Search; YouTube; the “Google Display Network” (which purportedly spans 35 million websites and apps); Facebook; Instagram; the “Meta Audience Network”; and a handful of others. In addition to their “free-to-use” nature, both platforms have long prided themselves on requiring no (or low) minimum budget requirements. Both platforms frequently offer free “ads credits” to get new advertisers started on these platforms, and up until recently, advertisers could set daily budgets of as little as $1 per day on either platform. Does any of this sound at all familiar?

Much has already been written, and will be written, on the subject of Google’s (alleged) price manipulation in ad auction, whereas the various tweaks and tunings Meta has been making to their “Meta Ads Manager” (and its underlying “Marketing API“) have gone relatively unremarked. And over recent months and years, both Google Ads and Meta Ads Manager have exhibited a distinct pattern, wherein new “features” are introduced, for the purported benefit of advertisers, but tend in actual fact to alter the ad auction dynamics in ways that maximise the seller’s profits, and the advertiser’s costs. Invariably, the new “feature” involves convincing advertiser to loosen some aspect of their existing rules about which ad impressions they’ve said they are willing to pay for. Then, after some more time has passed, another new platform update will promote the new feature to the “default experience”, but with an option to opt-out typically buried in some obscure sub-menu…

In some cases, advertisers have even seen existing platform features and functionality removed altogether, as recently happened with Meta Ads Manager’s “Inspect Tool” (RIP: 2019–2022), or the deprecation of detailed targeting exclusions across all of Meta’s ad-buying surfaces. That latter example actually makes for an excellent case-in-point, so I’d like to unpack it a bit further.

You see, the ability to keep users who fall into some given “detailed targeting” segment (or segments) out of the audience one targets with their ad campaigns has been both useful and necessary to coax certain insights out of Meta’s (frankly quite limited) campaign delivery reporting. Let’s suppose that you are marketing a product that is “made for everyone”, and so the “target audience” of your marketing efforts is somewhat loosely defined. Now, let us further suppose that you – or your bosses – become curious at some point as to whether (and how) your ads are resonating among new and expecting mothers, specifically.

When it comes to Facebook and Instagram, these “new moms” are a pretty simple audience cohort to define, identify and target; Meta Ads Manager offers plenty of straightforward methods and tactics by which you could do so. The difficulty lies in how Meta’s campaign delivery reports will not surface any detail as to which specific “detailed targeting” segments the users who saw your ads fell under (unlike Google Ads, which has long offered a feature called “observation targeting” for this very purpose). So how can you, the advertiser, go about figuring out whether “new moms” are responding any differently than any of the other audiences your ad campaign reaches?

Well, what you might have done (before Meta removed the ability to do so) is rig up two separate campaigns, identical in almost every respect, except that the ad-sets nested under one of these would exclusively target users who are known/inferred to be “new moms”, while the ad-sets nested under the other campaign would expressly exclude those same users. These two campaigns could then be run as a formal “A/B test”, and depending on how well that test was designed and executed, you might even gain some actual knowledge for your efforts.

Of course Meta’s ads systems would still militate against your learning anything useful from the test – so-called “Advantage detailed targeting” introduced new hurdles and noise to such testing, and by default Meta will try to declare the “winner” of an A/B test with a confidence interval as low as 65 per cent, which is a bit like saying “and I’m only ever wrong once out of every three tries” – but knowledge could still be arrived at, regardless.

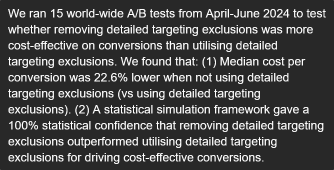

But this was all back in June 2024 — ancient history to us now. When they announced the removal of detailed targeting exclusions, Meta even went as far as asserting “100% statistical confidence” that by breaking the existing capabilities of their Marketing API, and forcing advertisers to accept less granular control of (and feedback on) their ad campaigns on Meta’s platforms, those advertisers would ultimately benefit from improved campaign “performance” and lower cost-per-conversion. So don’t worry, darlings.

Imitation is the Sincerest Form of Larceny

And that’s… well, that feels like as good a place as any to wrap this up. I see vanishingly little to gain from attempting fair-minded debate with any party who claims “100% statistical confidence” in their position, and much less so when they manage to do so with a straight face. To quote the only charming Nazi: “We simply aren’t operating on the level of mutual respect I assumed”.

During the company’s most recent quarterly earnings call, Meta Platforms’ CEO Mark Zuckerberg said something else that I found telling. He told the assembled investors:

AI is also going to significantly evolve our services for advertisers in some exciting ways. It used to be that advertisers came to us with a specific audience they wanted to reach — like a certain age group, geography, or interests. Eventually we got to the point where our ads system could better predict who would be interested than the advertisers could themselves. But today advertisers still need to develop creative themselves. In the coming years, AI will be able to generate creative for advertisers as well — and will also be able to personalize it as people see it. Over the long term, advertisers will basically just be able to tell us a business objective and a budget, and we’re going to go do the rest for them. We’re going to get there incrementally over time, but I think this is going to be a very big deal.

First of all, it is farcical that anyone at Meta, much less its CEO, would suggest that its ads systems show (or have ever shown) an ability to “better predict who would be interested than the advertisers themselves”. If anything, these systems have shown an aptitude for gently conditioning and re-conditioning advertisers, as a distinct subset of Meta’s overall user-base, into modifying their purchasing behaviours and/or business relationships in ways that ultimately profit Meta. The company has ample internal evidence for that aptitude, I am certain, and one imagines the company’s investors would prefer to discuss and evaluate these systems in line with their more fundamental business purpose: namely, bilking as much revenue as possible from the pockets of each individual paying advertiser.

Secondly — as if the analogy I have been drawing to the mob-run “numbers games” of old wasn’t yet clear enough — Zuckerberg’s comments on the future of the publisher-advertiser relationship make those parallels explicit. According to his perspective (and therefore as a matter of corporate policy), the ideal procedure for advertisers to interact with Meta’s ad systems would be indistinguishable from the procedure when one visits a wishing well: simply whisper your hopes and dreams, and then make your offerings, and in a little while Meta will be back to tell you how many of those dreams they are responsible for having made come true.

Perhaps we will even exclaim: How can I ever thank you?

¡uᴉɐƃɐ llᴉʞ I ǝɹoɟǝq ‘ǝɯ (ǝʇɐlnƃǝɹ puɐ) ɥɔʇɐɔ ǝsɐǝlԀ :∀