At a time when free and fair elections are a concern in democracies around the world, we need to be vigilant when it comes to ours being undermined.

— Kelvin Goertzen, 23rd Premier of Manitoba, 23 August 2019

Thus was I, sleeping, by a brother’s hand,

— The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark; Act I, Scene V

Of life, of crown, of queen at once dispatch’d:

Cut off even in the blossoms of my sin,

Unhous’led, disappointed, unanel’d;

No reckoning made, but sent to my account

With all my imperfections on my head.

O horrible! O horrible! most horrible!

If thou hast nature in thee, bear it not.

I agonised a bit while drafting this post, over which of the two quotations above I wanted it to begin with. In the end – as you see – I opted for both. I won’t get into my reasons for including the latter quite yet, but I promise you, we’ll get there.

As for the former, you’d be forgiven for assuming that Goertzen – then serving as Manitoba’s education minister, and currently as its Minister of Justice and Attorney General – had been speaking to any number of issues which had bubbled up into the public consciousness circa 2019.

Was he referring to Russia’s alleged (and by then, largely substantiated) attempts to interfere in the 2016 United States elections, a great many of which are purported to have been bankrolled by (the late) Yevgeny Prigozhin?

Perhaps he was alluding to the activities of Cambridge Analytica during that same U.S. election, and the bombshell revelations made by company insiders Christopher Wylie and Brittany Kaiser? The release of The Great Hack via streaming service Netflix just one month prior – a glitzy, but good documentary film on the role of emergent “microtargeting” tactics in the successful ‘Vote Leave’ campaign in favour of Brexit, and of Trump’s 2016 US presidential run – would certainly have thrust such topics front-and-centre in the minds of at least a few local voters.

Or might the Minister’s comments betray some heretofore unacknowledged insight into the – alleged – efforts by the Chinese Communist Party to – allegedly – interfere in Canada’s federal election later that same year, efforts which were – allegedly – actively underway at the time of Goertzen’s speech?

The answer, as it turns out, was D: none of the above. The quote comes to us instead from a press conference arranged by the provincial Tories during the 2019 Manitoba general election, during which Minister Goertzen announced that his party had lodged a formal complaint with the provincial elections commissioner.

The Tories were alleging that Unifor – a trade union, registered as a third-party political advertiser for that election – had spent more than $25,000, the limit then imposed by the provincial election financing law, on the purchase of “at least seven billboards”, each bearing the message: “Don’t let Pallister wreck health care”.

“It’s not just the rental time that they’re there,” Goertzen said, pleading his party’s case to the assembled press from the dais, “but it’s also the production and the installation costs”. Goertzen insisted that the Unifor billboards ought to be taken down straightaway, and that no other penalty envisaged by The Elections Financing Act would be sufficient.

“If they are exceeding the limit,” he said, “it can really have an impact on elections. And the ability to solve that and to have a recourse for that is simply a fine after … votes may have already been influenced.”

Unifor’s regional director would call the Tories’ complaint “desperate” and “a laughable distraction”; the union later filed expense reports, as all third-parties are obligated to do, which showed costs of about $19,000 for electoral advertising during that election period. Manitoba’s Commissioner of Elections would eventually (and quietly) dismiss the PC Party’s complaint, about a year later.

That was then; this is…wow.

In the first of my (planned) trio of posts on the Manitoba 2023 election, I described at some length a recent $50,000 Meta Ads campaign (nevermind the robo-calls and mailers) paid for by the “Canada Growth Council”, to deliver partisan ads attacking Manitoba NDP leader Wab Kinew (plus a handful of other sitting NDP MLAs) to Winnipeg voters throughout May and early June of this year. I also expressed some skepticism at that time as to the Premier’s (and her party’s) knee-jerk denials of having had any hand in, or knowledge of, the CGC’s political activities in Manitoba.

(As a brief coda to that post, subsequent reporting by PressProgress’ Emily Leedham would seem to have borne out a great many of my suspicions on these fronts. Canada Growth Council did ultimately register as a third-party (as is required of all advertisers with more than $2500 in “election communication expenses” during the “pre-election period”), however their “Manitoba Watch 2023” account has also fallen silent, ever since the start of the formal “pre-election period”. See you next time, fellas!)

For this second installment in the trilogy, my original plan was to provide an update on the “state-of-play” when it comes to (online) political advertising among Manitoba’s main political parties, shortly after the writ had formally been dropped, and the official “pre-election period” had ended.

But then…well. The plain truth is, over this summer and leading up to the writ-drop, none of the registered parties really seemed to be doing anything – at least nothing much worth blogging about, and certainly not worth reading a blog about. I also got burned out of my apartment around mid-August, so that ended up adding another week or two to my (personal) deadline for publication.

Oh, sure, I probably could have made things easier on myself. Punched out a couple hundred words about something weird and small, like the case of Efficiency Manitoba, the Crown corporation which – despite having not advertised via Meta Ads since at least 2020, and perhaps never having done so since its creation by the Pallister government in 2017 – has trafficked and flighted more than one hundred unique ad creatives since the start of June.

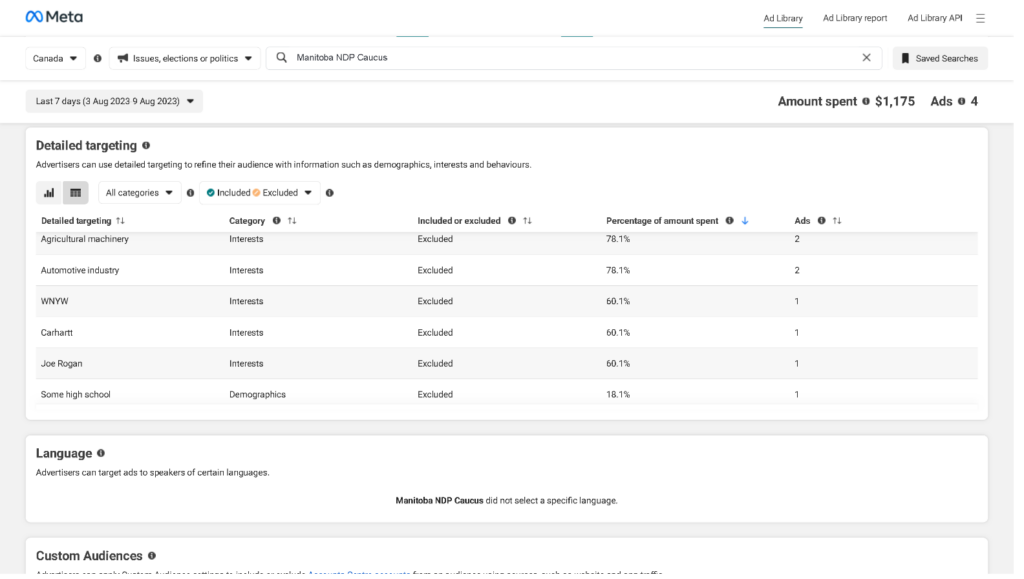

Or I might have “made hay” over the somewhat baffling decision, recently taken by both the Manitoba NDP and the Manitoba NDP Caucus, to exclude Facebook and/or Instagram users who show interests in “agricultural machinery” from seeing their ads. But I’m honestly not sure how long I could go on writing on the topic before it takes on the quality of whispering something, through clenched teeth, while standing three inches from your face, unblinkingly.

…But hey, since we’re here: say there, Dippers, how does that old song go again, eh? Come on something, soldier, some-or-other, from the mine and factory?

No, even with these, we’d still only be talking about a few hundreds, maybe thousands of dollars in dubious political media-spend – small potatoes, in the grand scheme of things. If this middle installment is going to offer any meaningful insight and/or clues as to how the 2023 Manitoba election might shake out [**spoilers ahead**], then we’re going to need to talk about…

The 800-Pound Bison in the Room

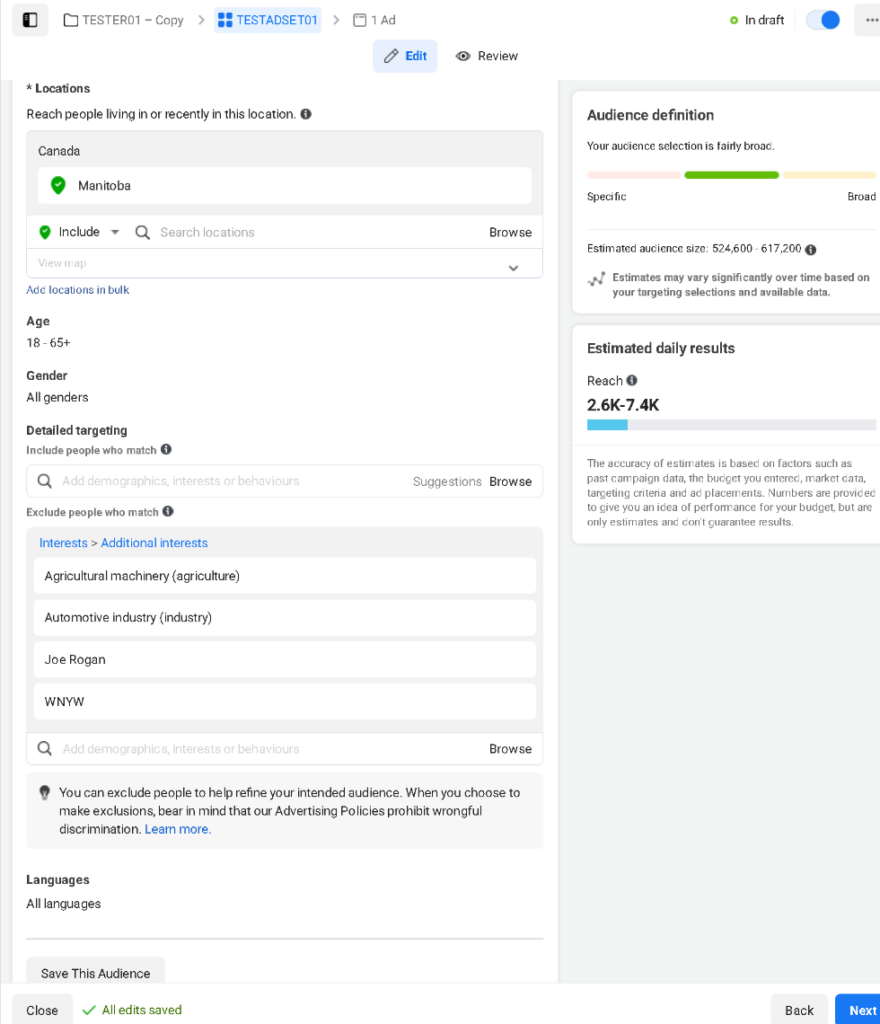

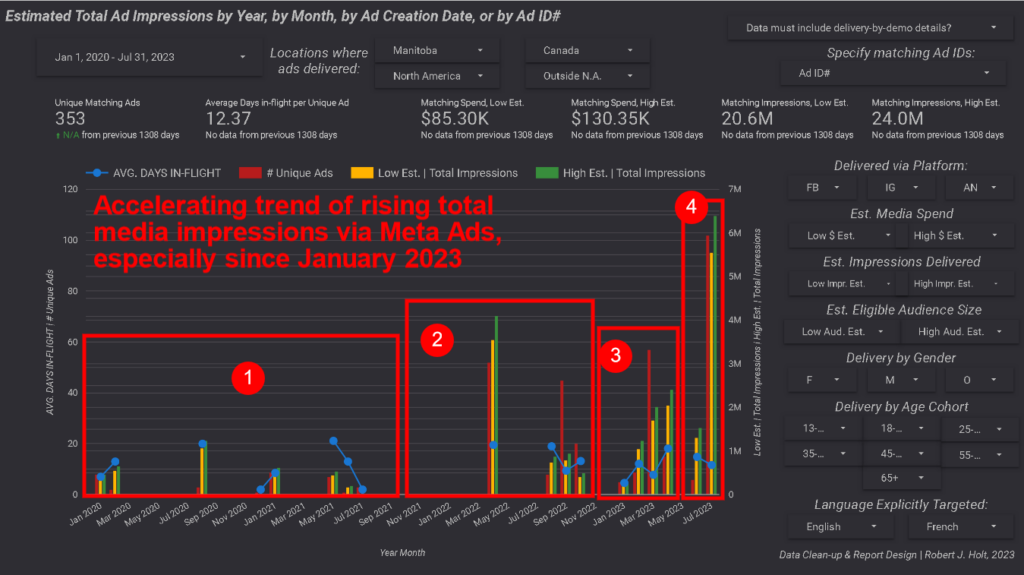

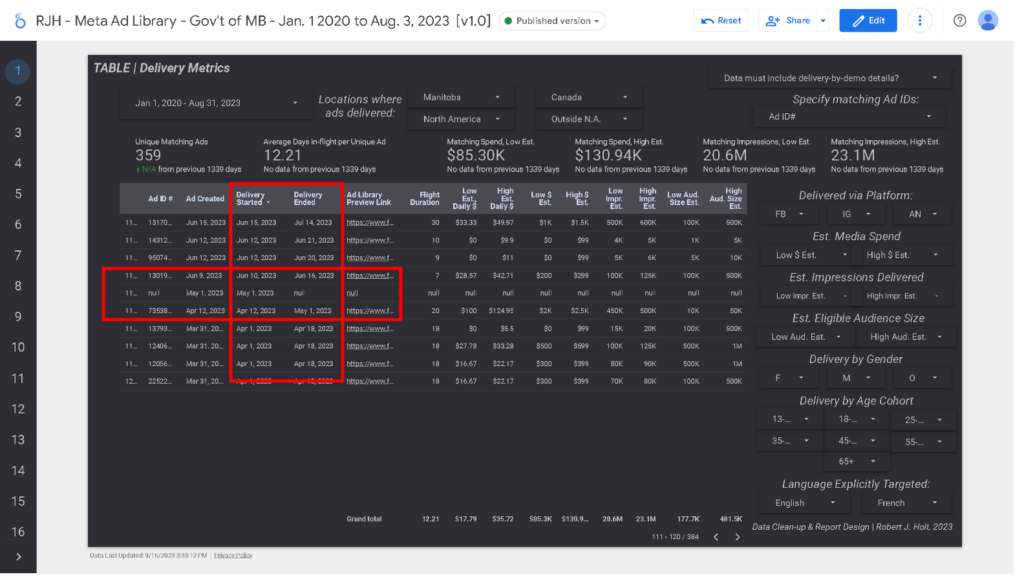

According to the Meta Ad Library report (see Figure 3, below), no single advertiser spent more during the first third of Manitoba’s formal “pre-election period”, on what Meta deemed as “ads about social issues, elections or politics” targeting users located in Manitoba, than the Government of Manitoba itself. The degree to which the Manitoba Government dominated the overall “universe” of political advertising within the province via Meta Ads over the summer was – in a word – remarkable.

There are, I’m quite certain, plenty of strange and noteworthy insights one might glean by poring over the full history of Meta’s Ad Library archive for the Manitoba Government’s official Facebook account. Yet in doing so, one quickly runs up against what is perhaps the single greatest limitation of the more ‘user-friendly’ UIs provided by Meta to access their Ad Library: they do a lousy job of surfacing insights on the overall activities of any given advertiser, over any timeframe other than:

- The past 7 days

- The past 30 days

- The past 90 days

- All time (in Canada, since approx. Q3 2019)

This largely precludes one from using the Meta Ad Library UIs to do such things as, say, compare how the Manitoba Government’s recent “political” advertising efforts leading up to the ‘election blackout’ period might differ from the approach and/or tactics applied to such public advertising campaigns in the past. To pull off something like that, one would have to go through a much more onerous process of verifying their identity to Meta, so as to gain access to the ‘Meta Ad Library API’, then make (and “clean“) all of the queries needed to compile a complete dataset on every “political” ad to have ever run through the Government of Manitoba’s official Meta account for which Ad Library data is available. And even after you’d managed all of that, you’d probably still want to build out some sort of reporting engine capable of turning all that data into charts and other visualisations, just to make all that data intelligible.

Anyways, I recently went through the somewhat onerous process of verifying my personal identity to Meta, so I could make calls to the Ad Library API, so I could pull (and clean up) a complete dataset on (almost) every “political” ad ever run through the Government of Manitoba’s official Meta account throughout the lifetime of the 42nd Legislature. I then whipped up a custom reporting engine to spit out some charts, so as to render the dataset intelligible. You can access that reporting engine – feel free to play around with it – here.

To save you the trouble of clicking your own way through it, though, I’ve also compiled a few of the more salient conclusions I’ve since drawn, after having sat with the reports (and their underlying dataset) over the past few weeks of design & development. To wit:

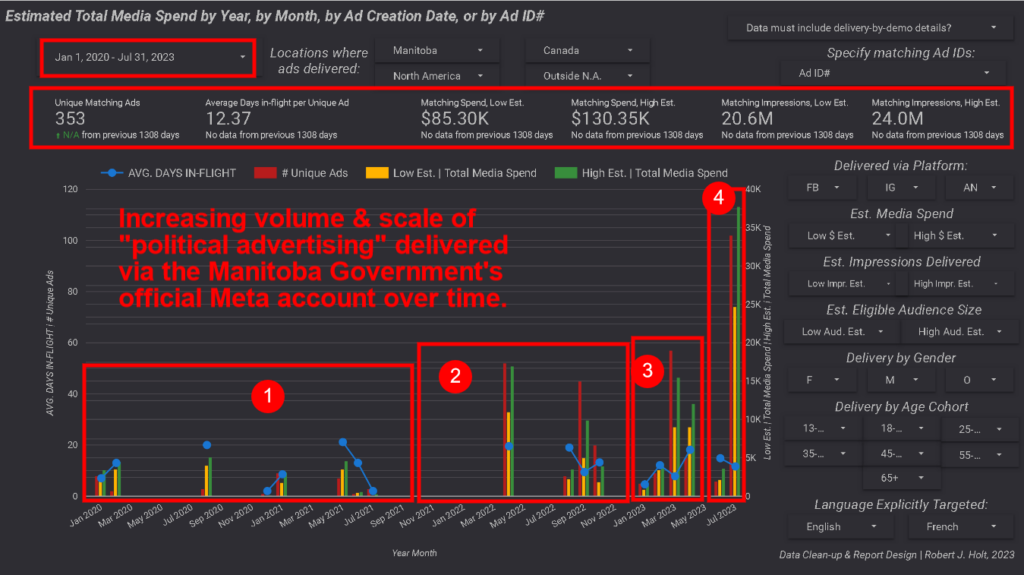

Defining “epochs” of the Manitoba Government’s political advertising via Meta Ads during the 42nd Manitoba Legislature

First things first: it is often useful, for purposes of analysis, to distinguish between periods (or “epochs”) based on some shared traits and/or qualities of the data at a given point in time. With regard to “political” ad campaigns executed via the official Meta account(s) of the Manitoba Government, I came to adopt the following system of classification:

Epoch I: “Late Pallister, Early Pandemic”

22 months, January 1, 2020 – October 31, 2021

- The earliest “political ads” for which Meta Ads Library data is available via the API were “in-flight” circa December 2019.

- For ease of comprehension, records from any ads created before Jan. 1, 2020 have been filtered/excluded from the “scorecards” found on all pages of the “reporting engine” described/linked above, and shown in the screens below.

- “Epoch I” spans from the earliest federal/provincial public health measures in response to COVID-19, to the earliest federal approvals for COVID-19 vaccines.

- Epoch end-date coincides with Heather Stefanson’s victory in the PC leadership race (Oct. 30, 2021) and her being sworn in as Premier (Nov. 2, 2021).

Epoch II: “Early Stefanson Period”

14 months, November 1, 2021 – December 31, 2022

- Several observed changes in strategy/tactics applied to “political” advertising, compared to the preceding period.

- Epoch end-date reflects several “year-end” interviews which Premier Stefanson gave to local news-media outlets in January 2023, in which the Premier suggested (to paraphrase) that her greatest challenges as Premier had been matters of “communication”, but also that steps had been, and were being, taken to “fix” this:

- Manitoba Government needs to do better job of highlighting accomplishments: premier, CBC News Manitoba, Jan. 11, 2023

- ‘Moving in the right direction’: Premier Heather Stefanson defends her government’s record on health care, dismisses predictions Tories headed for election defeat in wide-ranging interview with Free Press, Jan. 11, 2023

Epoch III: “2023 Pre-Pre-Election Period”

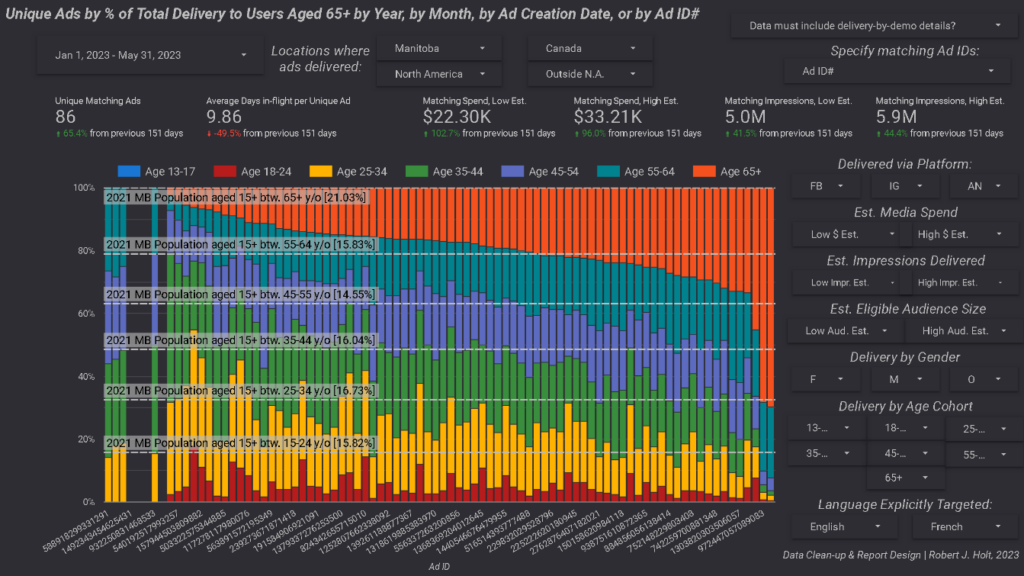

5 months, January 1, 2023 – May 31, 2023

- Several observed changes in strategy/tactics applied to “political” advertising, compared to the preceding period.

- Epoch end-date coincides with the start of the formal “pre-election period”.

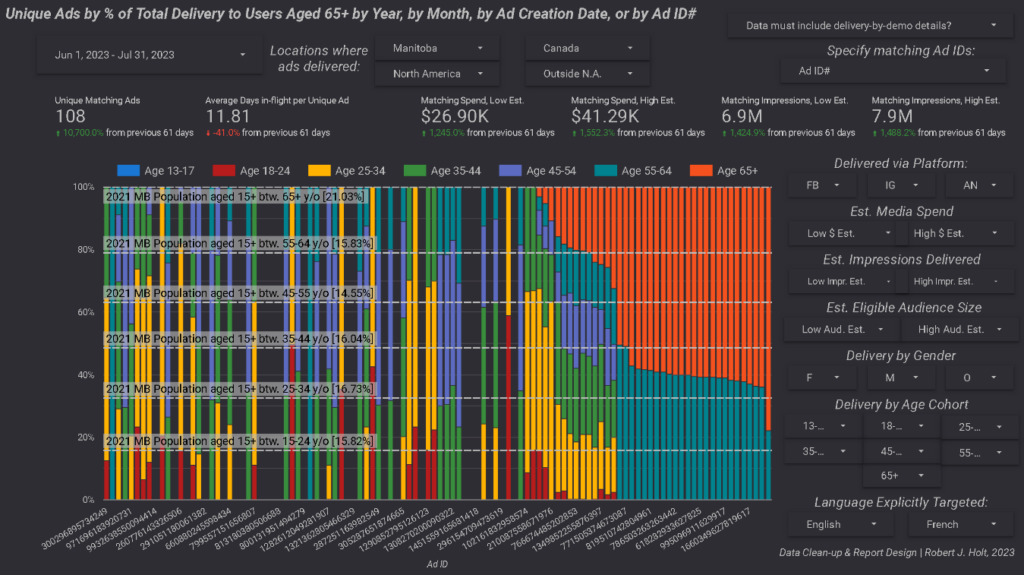

Epoch IV: “2023 Pre-Election Period”

2 months, June 1, 2023 – August 3, 2023

- Per Elections Manitoba, the “pre-election” period began on June 7, 2023.

- Per the Meta Ad Library, no MB Gov’t ads were in-flight between May 1 and June 10. Pin this in the back of your mind; we’ll come back to it.

- Still further significant observed changes in the strategy/tactics applied to political ads run via the Government’s official Meta account(s).

Comparing the scale, volume, and substance of political advertising by the Manitoba Government via Meta Ads during the 42nd Manitoba Legislature

The four “epochs” described above will perhaps make more sense through reference to some charts produced by the ‘reporting engine’. Below are a pair of screens illustrating the total number of unique ads trafficked per month, as well as the low/high estimated total spending on these ads, or estimated total impressions delivered, per month of ad creation.

Following these, I’ve included a brief chronological list of “notable campaigns” during each epoch, to provide some context as to what kinds of “political” advertising the Manitoba Government has engaged in over the course of the past three and a half years. Click the subheadings below to access those.

Notable campaigns during “Epoch I” included…

- ~$5,000–$7,500 spent promoting the 2020 provincial budget;

- ~$3,500–$4,500 spent promoting the Manitoba-Québec Exchange Program for French Immersion students in Grades 10 or 11;

- ~$2,000–$2,500 spent promoting “The #RestartMB Pandemic Response System“;

- ~$2,000–$2,500 spent promoting the ability of Manitobans to purchase hunting licenses, fishing licenses, and/or park vehicle permits online;

- ~$5,000–$7,500 spent promoting the 2021 provincial budget;

- ~$3,500–$4,500 promoting the “Better Education Starts Today” plan; and

- ~$500–$600 spent encouraging Manitobans to be vaccinated against COVID-19.

- NOTE: I’m not aware of any pandemic-specific Meta accounts/identities which the Manitoba Government may have set up to execute public advertising campaigns related to the its response to COVID-19, and/or to provincial efforts to vaccinate the population. What I do know is that any such campaigns were unlikely to have been run through the regional health authorities, considering that the WRHA has run no ads via Meta Ads since 2019.

Notable campaigns during “Epoch II” included…

- ~$5,500–$9,000 spent promoting the 2022 provincial budget;

- ~$5,250–$7,750 spent promoting the availability of free COVID-19 rapid testing kits “at many retailers”;

- ~$2,250–$3,500 spent soliciting nominations for the 2022 “Empower Women Awards“;

- ~$3,250–$5,250 spent touting the “Manitoba Affordability Package”, a set of one-time cheques for $250 or more mailed to Manitoban families; and

- ~$3,500–$8,000 spent promoting a new “strategic plan for healthy and active lives for seniors”.

Notable campaigns during “Epoch III” included…

- ~$9,000–$15,000 spent promoting the 2023 provincial budget;

- ~$2,000–$2,500 spent promoting a financial support program made available through Accessibility Manitoba;

- ~$6,600–$11,500 spent promoting the “Historic Help for Manitobans” public awareness campaign; and

- ~$9,500–$13,250 spent promoting government investments in various “community grant” programs.

Notable campaigns during “Epoch IV” included…

- ~$3,000–$5,000 spent on a public awareness campaign re: healthcare staffing, with most ads bearing the tagline “Retain, Train, Recruit”;

- ~$3,500–$5,500 spent promoting Manitoba’s Bilingual Service Centres;

- ~$3,000–$6,000 spent on public awareness campaigns, with most ads bearing the tagline “Healing Healthcare: A Recovery Plan”;

- ~$10,000–$12,000 spent promoting Government funding commitments related to education; and

- ~$500–$1,500 spent promoting a grant program which partially covers the cost of hearing aids for Manitoba seniors.

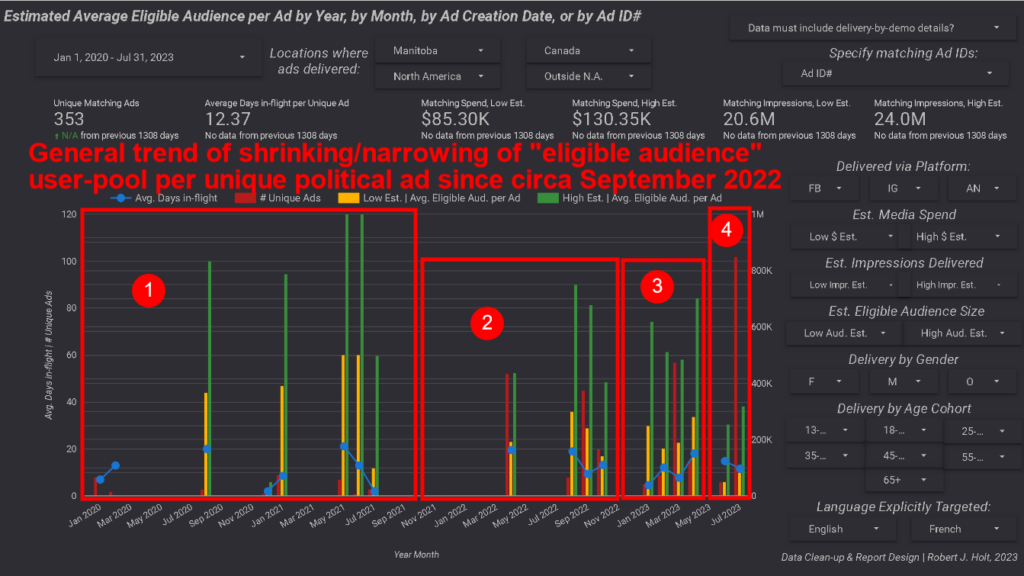

Comparing the use and prevalence of ‘microtargeting’ tactics by the Manitoba Government via Meta Ads during the 42nd Manitoba Legislature

“Microtargeting” – as the very first sentence of its Wikipedia entry will tell you — “is the use of online data to tailor advertising messages to individuals, based on the identification of recipients’ personal vulnerabilities”. You’re not likely to find a better summary of the concept than that. I certainly haven’t.

We need not burden ourselves with a lengthy discussion on the “shoulds” and “shouldn’ts” of using such tactics in political advertising, and/or in online marketing more generally. It is [insert current year]; folks will approach these issues from varying perspectives, and some of them even do so in good faith.

That being said, a ready consensus might perhaps be found amongst Manitobans for the idea that, as a rule of thumb, any ‘microtargeting’ of public advertising campaigns (ie. those undertaken by the state, and using public funds) should be only as granular as is necessary for the efficient delivery of the services/programs being promoted.

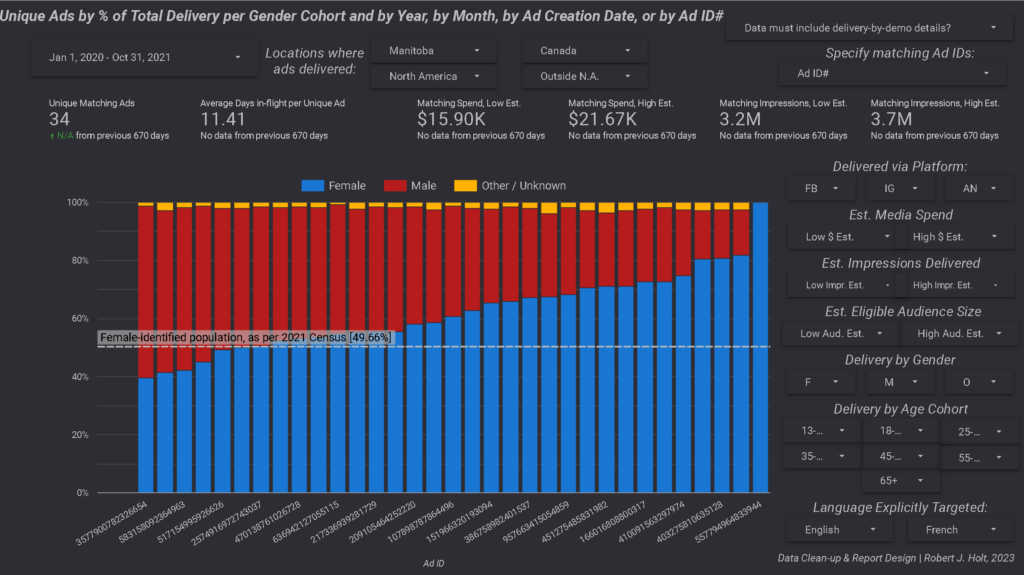

What I mean by that is, if the Government intends to promote a service aimed exclusively at Manitoba seniors, say, then it makes sense that such advertising campaigns could be targeted specifically at users of Meta’s platforms who are known/inferred to be over the age of 65. But if the government program being promoted serves a more “general public” mandate, then the delivery of that messaging ought reasonably to correspond (at least roughly) with the age and gender distributions found in the total population.

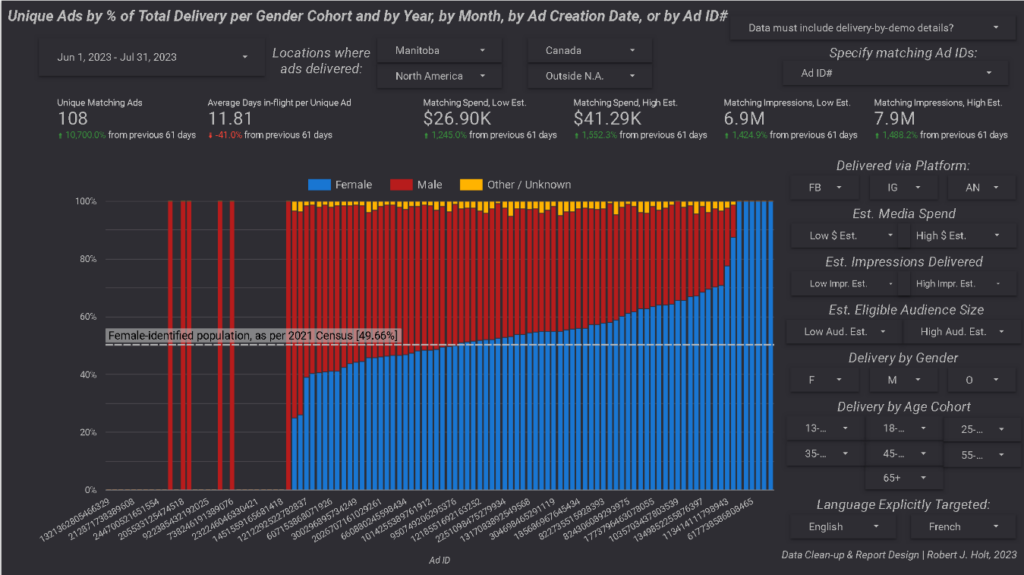

As you’ll see through the charts below, there has been an ongoing trend away from targeting broad “general audiences” in the range of 500k-1M Meta accounts (e.g. “Manitobans aged 18+”) and towards tailoring individual creative/messaging variants more granularly towards specific subsets of Meta users(eg. Manitoba females above the age of 55), going back as far as August 2022.

It should also be noted that the frequency with which “microtargeting” tactics were applied to (ostensibly) public ad campaigns run via the Manitoba Government’s official Meta account(s) spiked during “Epoch 4”. Some tactics, for example targeting certain ad creatives specifically to users known/inferred to be male, were not observed during any prior ‘epoch’ of the Ad Library records – these dating back nearly four years.

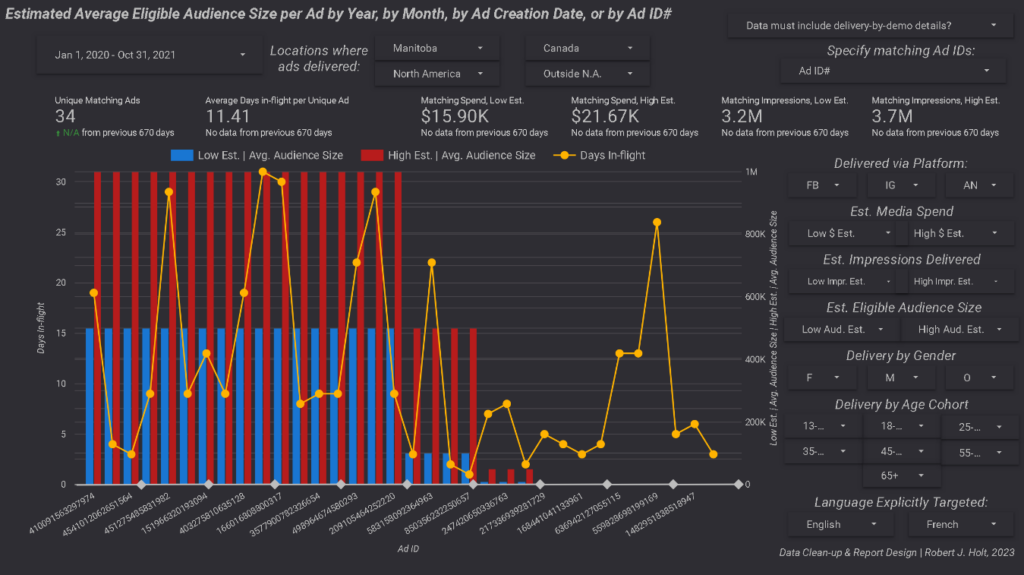

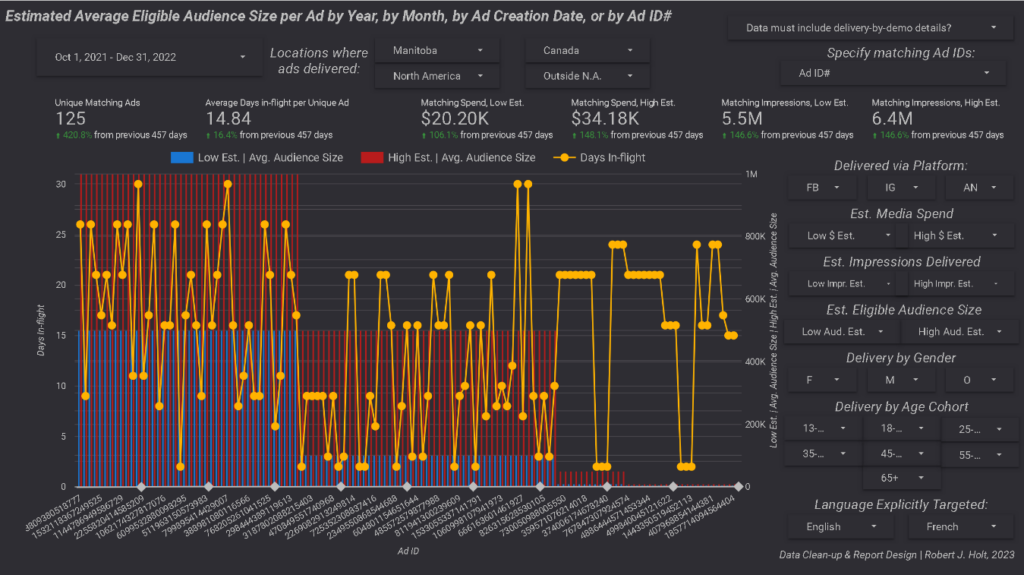

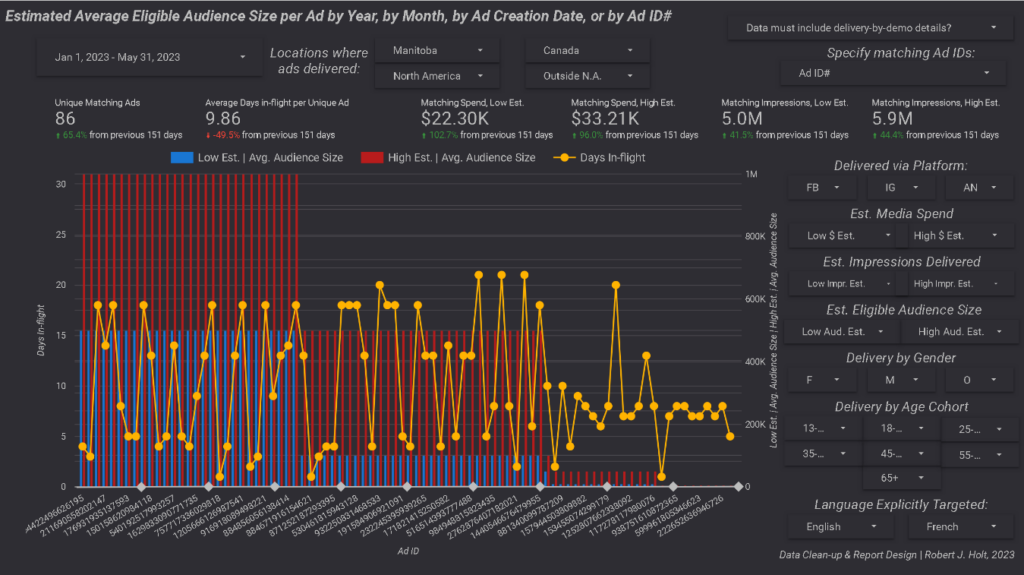

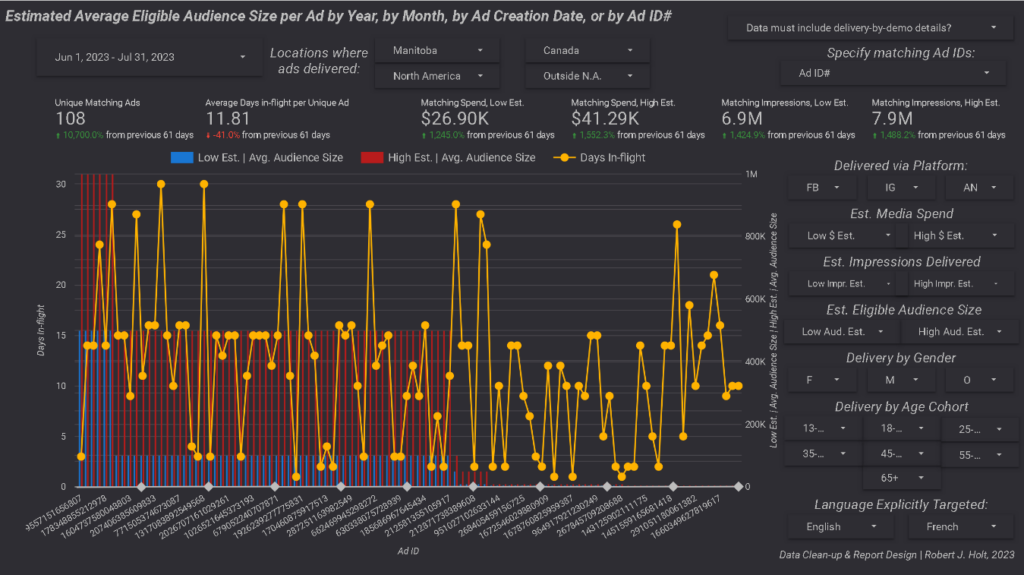

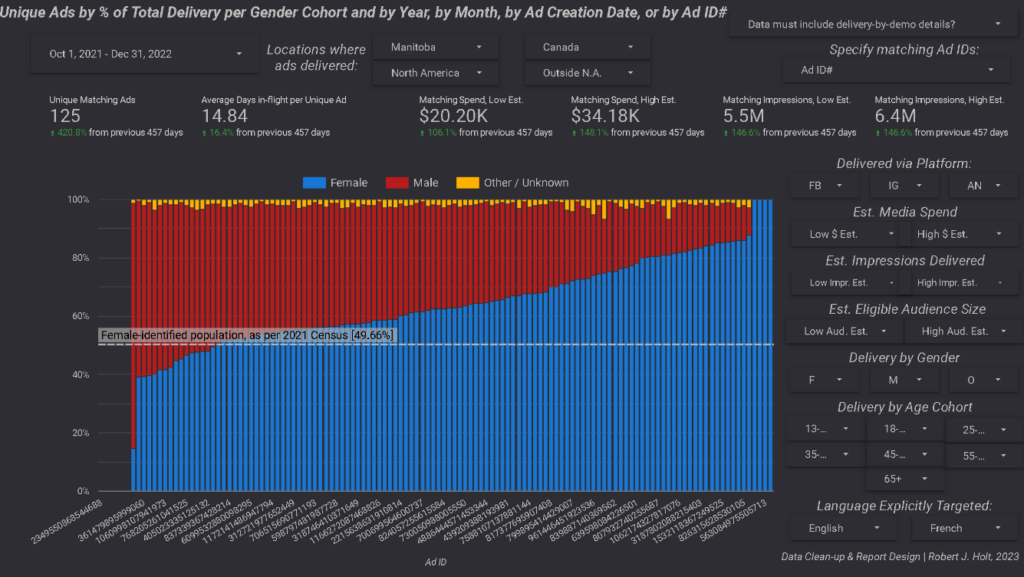

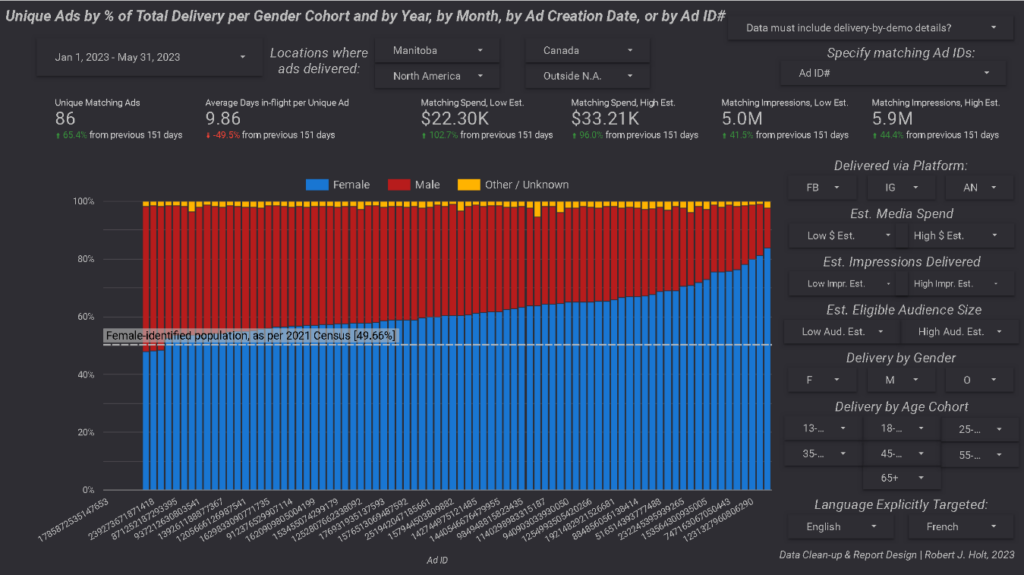

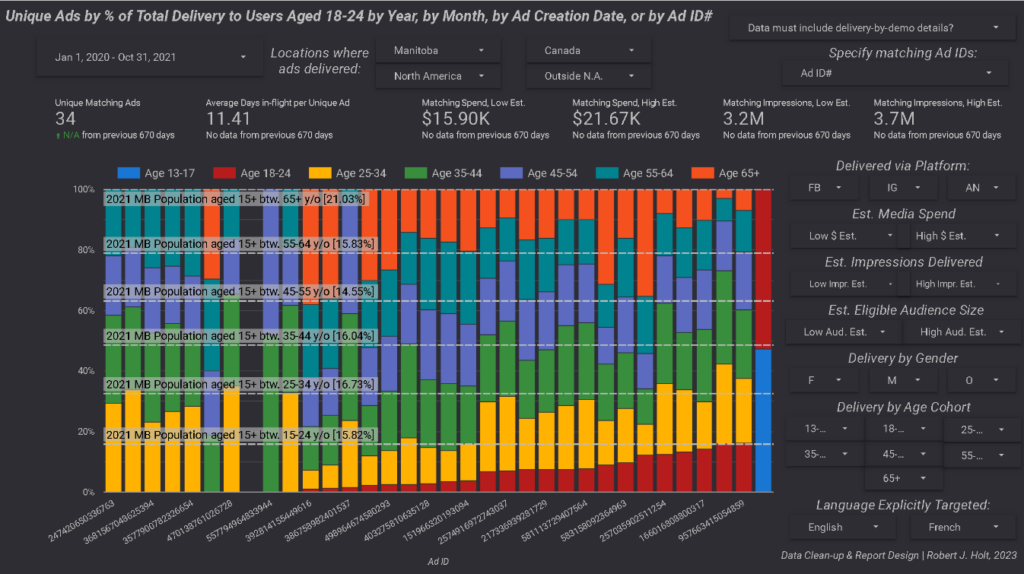

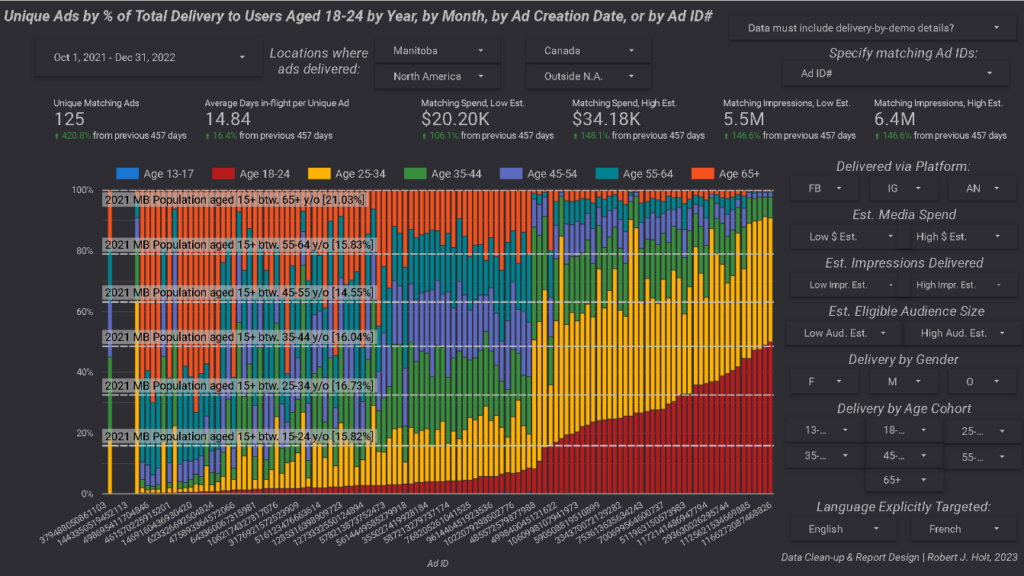

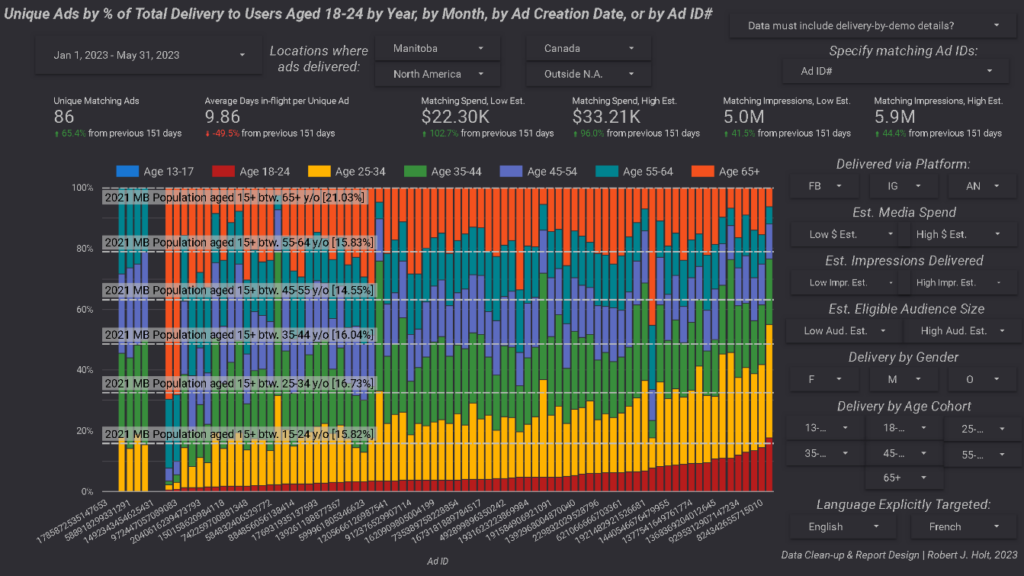

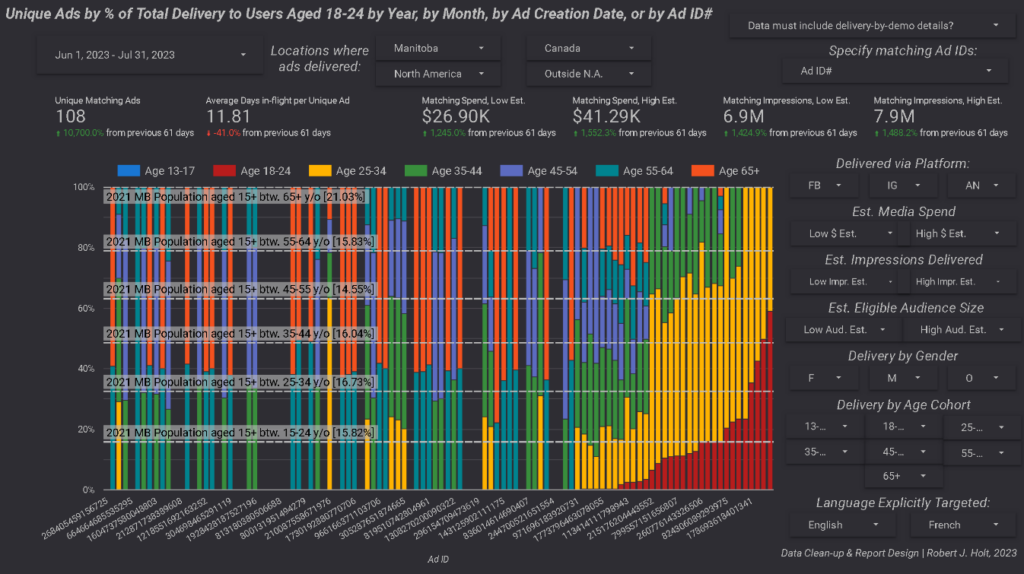

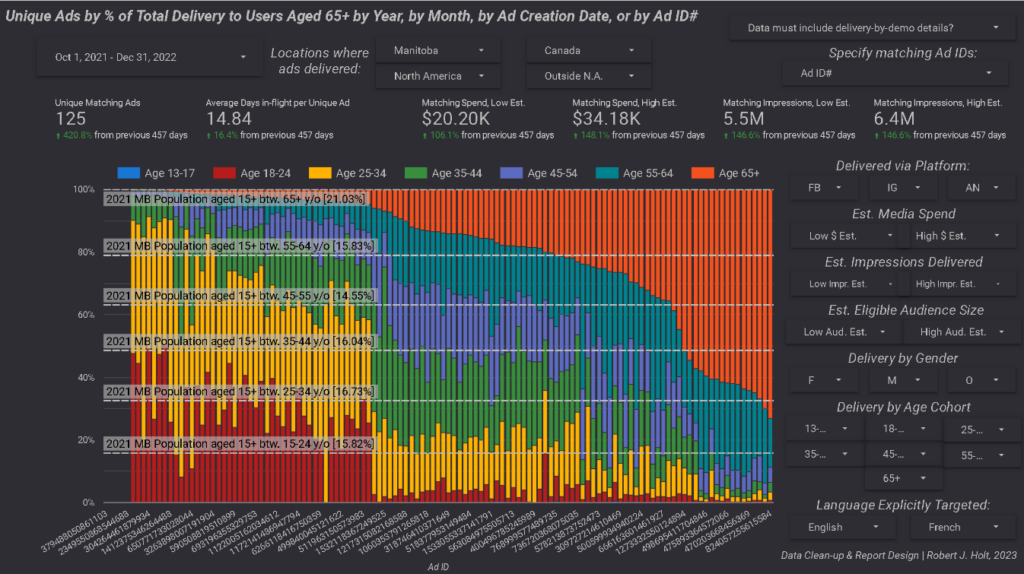

Figure 6 below shows a month-by-month average of low/high estimates for “eligible audience size” per unique ad, whereas Figures 7 shows the eligible audience sizes of each unique “political” ad, per epoch, in descending order. After these, Figures 8-10 show the proportion of impressions delivered, per unique ad and broken down for each epoch, on the basis of gender cohorts (Figure 8), 18-24 year olds (Figure 9), and seniors (Figure 10).

Figure 7: Estimated Eligible Audience Size per Unique Ad by “Epoch”

Figure 8: Unique Ads per ‘Epoch’ by Proportion of Impressions Delivered per Gender Cohort

Figure 9: Unique Ads per ‘Epoch’ by Proportion of Impressions Delivered to Users aged 18-24

Figure 10: Unique Ads per ‘Epoch’ by Proportion of Impressions Delivered to Users aged 65+

All political ads run via the Manitoba Government’s official Meta account(s) were paused during the Canada Growth Council’s partisan advertising campaign

Posted without further comment.

Impact of microtargeting on language employed by the Manitoba Government in political advertising via Meta Ads in 2023

I’d like to apologise if, up until this point, this has all seemed terribly abstruse. Hopefully I’ve managed – at the very least – to make clear my belief that something is happening here, that it’s something Manitoba has not encountered before and that people ought to be paying attention.

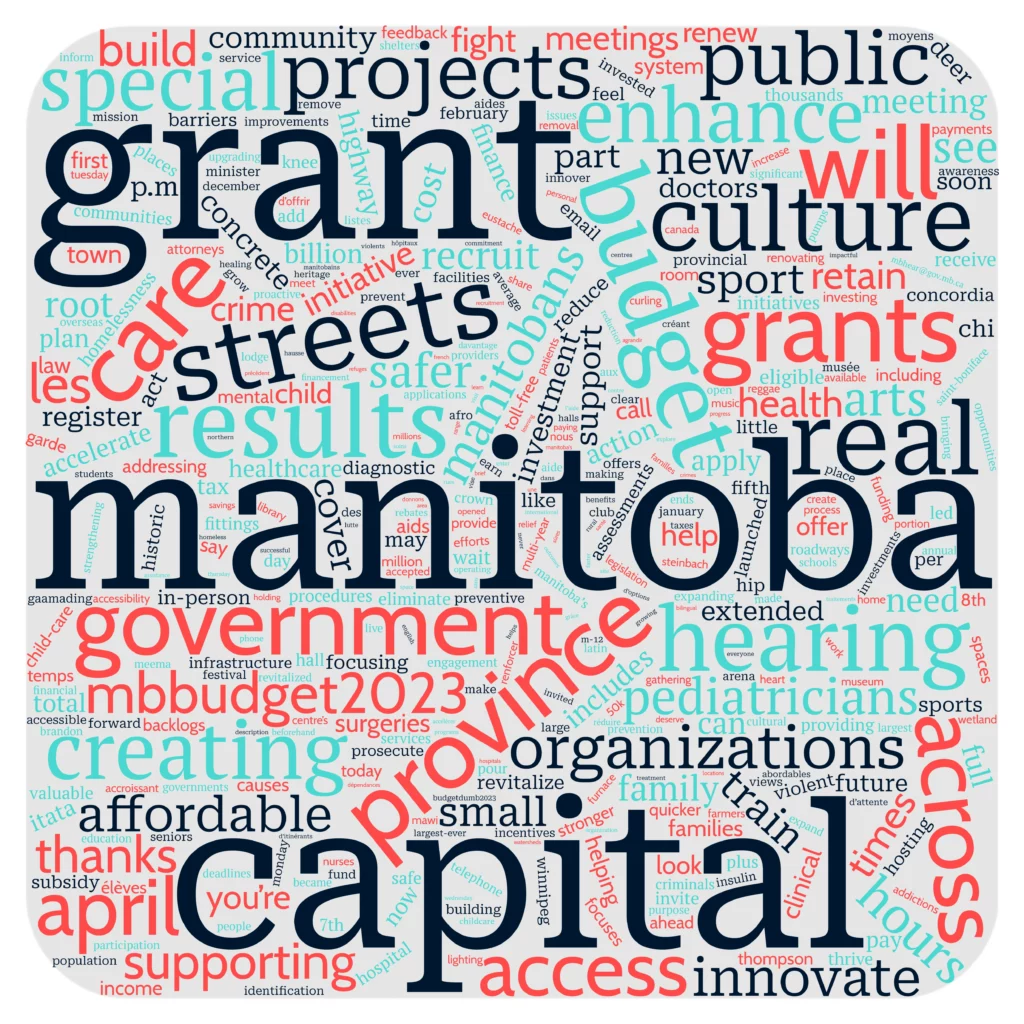

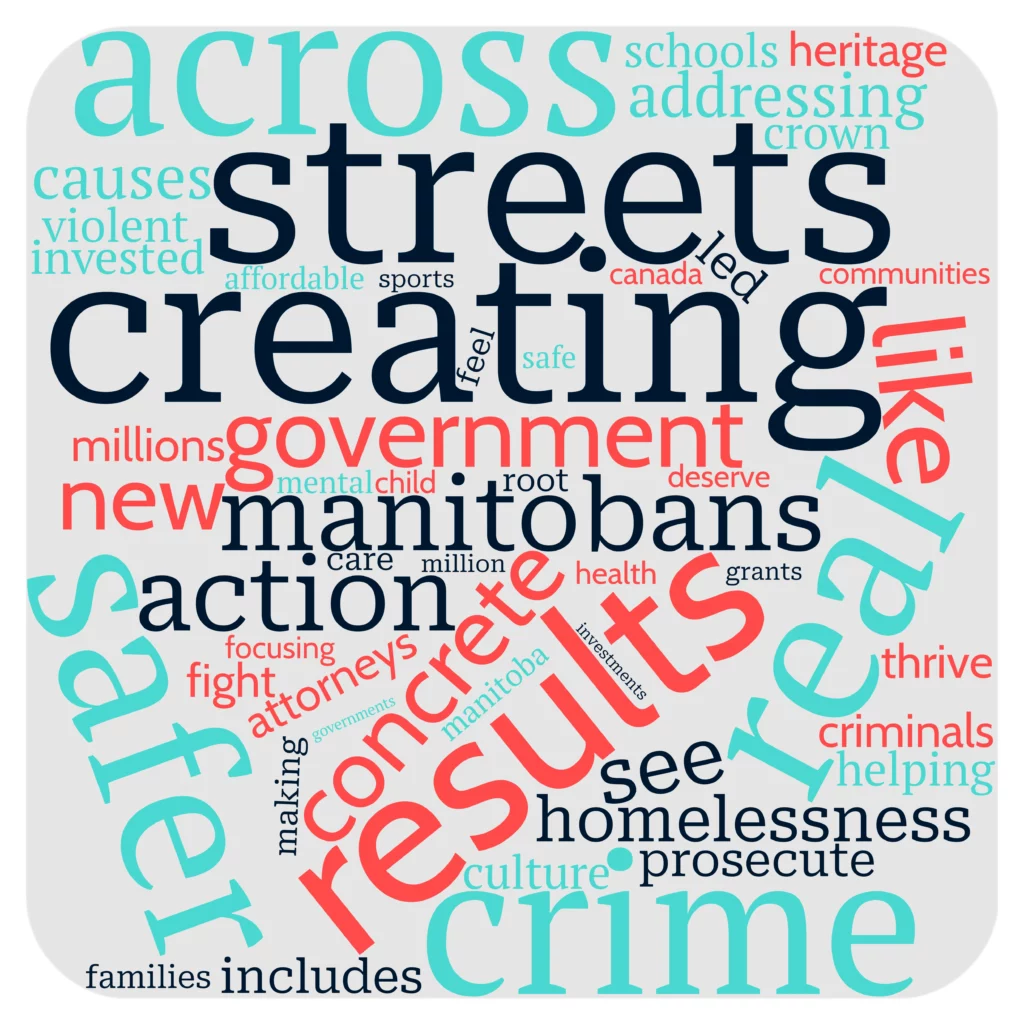

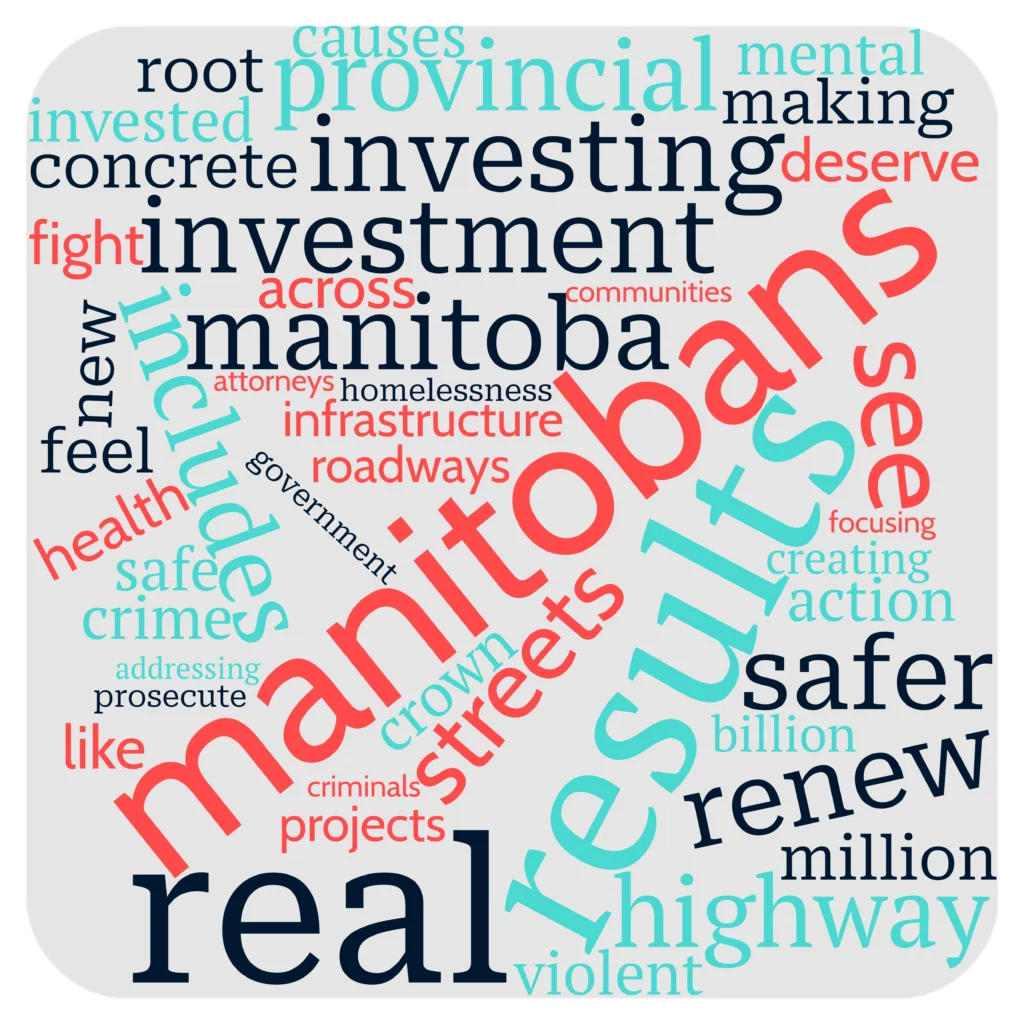

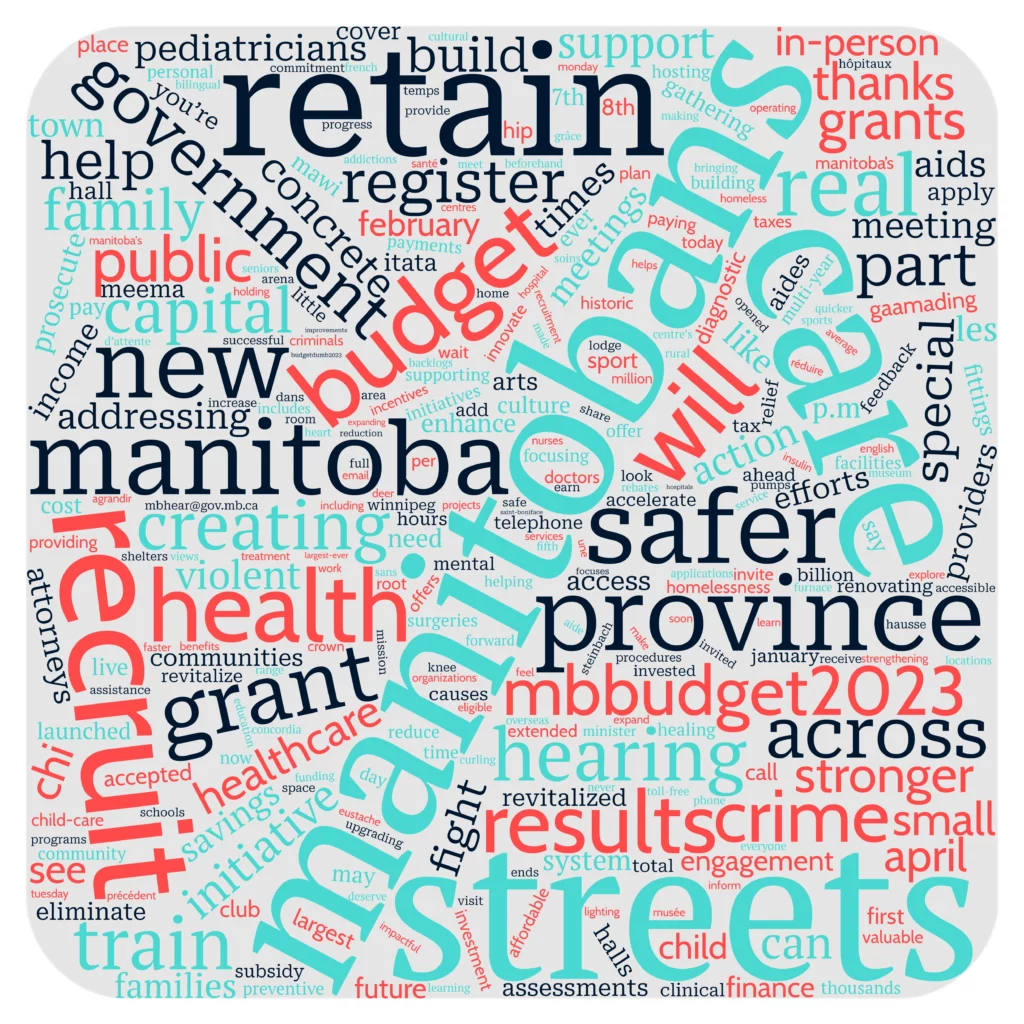

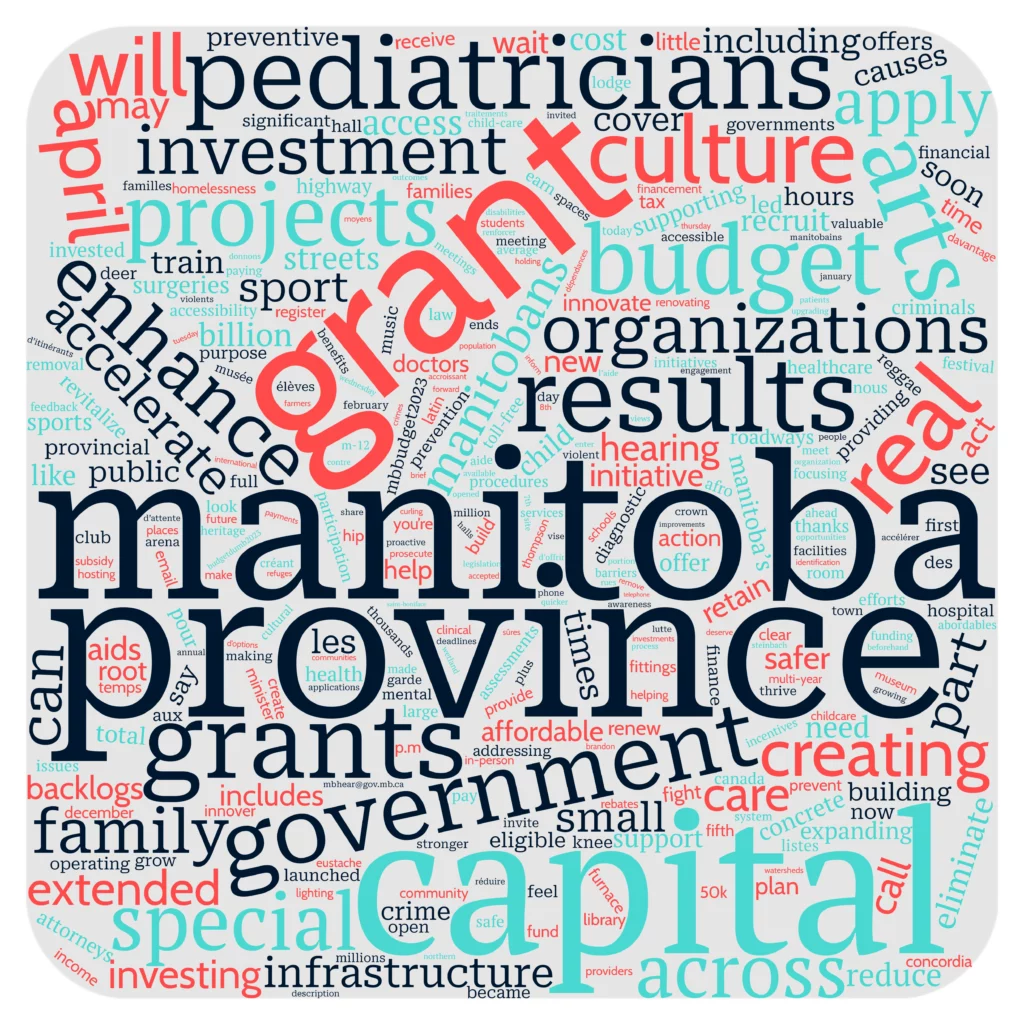

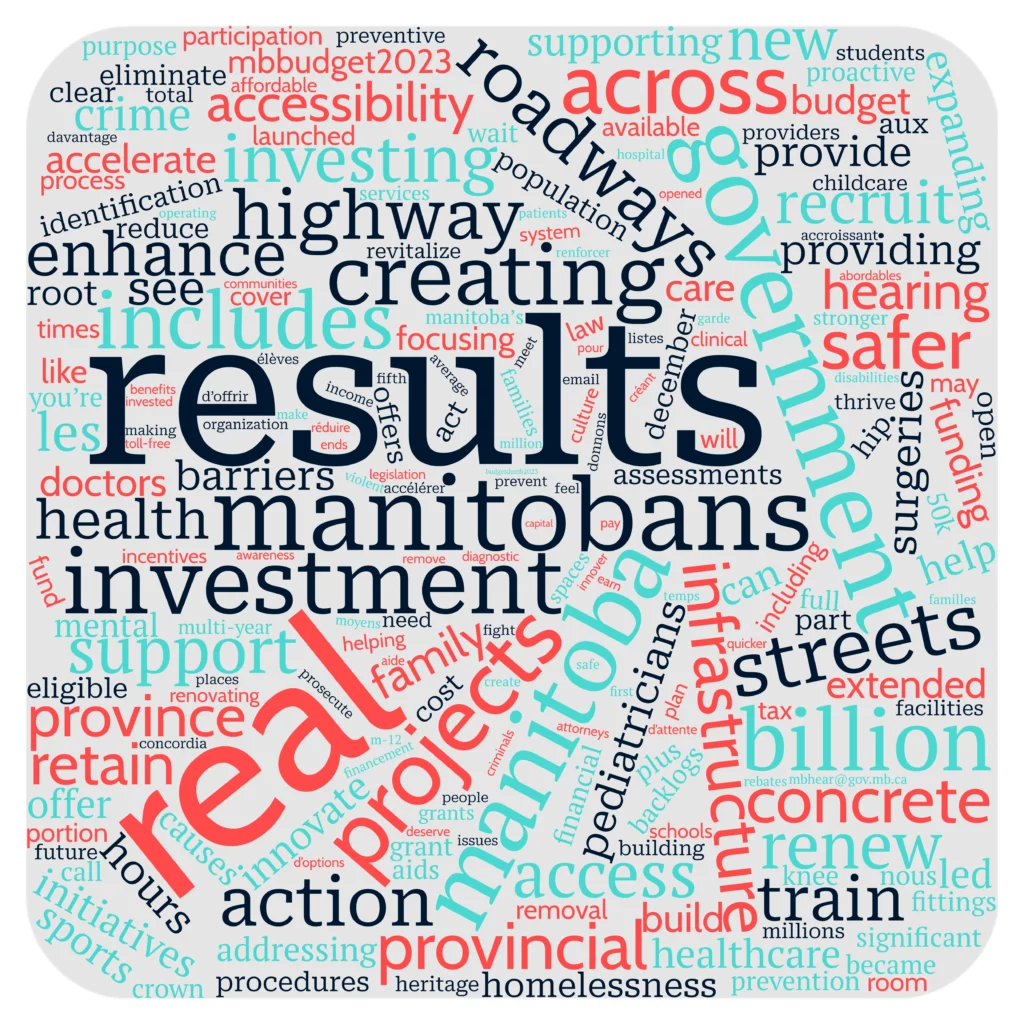

To drive these points home, I decided to take my analysis one step further, and produce a number of “tag clouds” based on the ad copy used in political ads which have run through the Manitoba Government’s official Meta account(s) in 2023 to-date. The resulting tag clouds can help us better understand not just who the Government’s various ‘target audiences’ have been, but rather what the Manitoba Government has tended to say to these audiences most often, and how the Government’s official messaging may have varied depending on their audience.

The first subhead below expands to show a tag-cloud of all (English-language) ads created during “Epoch III” and “Epoch IV”. The second subhead features tag clouds specific to those ads which saw their delivery “overindex” towards either male or female audiences, in order to compare them. The third section features tag clouds of ads with delivery which overindexed/underindexed towards various age cohorts.

Note that, as with all subsequent tag-clouds below, the size of each term corresponds with how frequently it appears, across all ad-copy text fields, within the given subset of Ad Library records. They have not been weighted on the basis on spend/impression volumes.

Terms used in English-language MB Gov’t political ads during “Epoch III” and “Epoch IV”

Terms used in MB Gov’t political ads where delivery “overindexed” to one gender cohort

Terms used in MB Gov’t political ads where delivery “overindexed” to one age cohort

“What did we learn, Palmer?”

…You know something? I’m beginning to suspect that somewhere down the line, it became trivially simple for ordinary folks (read: civil society) to just straight-up reverse-engineer the advertising strategies and tactics of major political parties, or just about any partisan political actors who might care to make any sustained effort at influencing their choices one way or another.

This is perhaps because, somewhere down the line, it did. The analysis I’ve prepared and presented above was drawn entirely from (more or less) publicly available sources, using entirely web-based tools, and a heaping tablespoon of what we tech wonks like to call “domain knowledge”. Pretty much anybody can do it. I did it. It wasn‘t all that hard. How is that? Why is that?

As a Manitoba resident, I have but two groups I must thank for the remarkable new degree of insight into my home province’s civic life which I (and hopefully you) now enjoy. First, and chiefly among these, is that ever-growing list of states and governments which have drafted, debated and adopted new privacy and other ‘digital rights’ laws in recent years – many of which have come to explicitly mandate such levels of transparency as the ‘minimum operating standards’ for their own digital economies.

The second group we must thank are the global tech giants themselves – in this case Meta, which for various reasons has become more-or-less the only game in town when it comes to political advertising online within Canada. Nothing legally obligates Meta to provide such granular records on the political advertising executed through their platforms when such efforts are directed at Manitobans; far from it, in fact. Rather, Meta currently extends the full feature-set and functionalities of the Ad Library to its Canada-based operations for the simple fact that limiting the platform’s functionality to the barest legal minimums required, in each legal jurisdiction in which they operate, would cost more to run. It’s less an act of beneficience on Meta’s part than it is one of accidental, negligent largesse.

And… well, here’s the thing: a little over four years ago, I wrote a post which briefly discussed how PIPEDA – at time of writing, still Canada’s governing federal privacy legislation for the private sector – came into being in the late 1990s, almost solely as a response to the EU’s adoption of the Data Protection Directive in 1995. That post went on to describe the next generation of privacy law emerging out of the European Union – the GDPR – and how this legislation advanced the digital rights (and economies) of EU citizens, while hinting at the kinds of protections Canadians seemed destined to enjoy soon (provided that Canada still intends on having some form of trade in services with any EU member-states, which, yenno, we Cana-do).

In the intervening years, a whole raft of privacy and data-rights laws have been passed all around the globe, significantly enhancing data rights and protections enjoyed by the residents of Brazil, Thailand, South Korea, New Zealand, and of numerous US states including California, Colorado, Connecticut, Virginia, Vermont, Utah… the list goes on.

Canada’s response to the GDPR, meanwhile – in the form of the federal Digital Charter Implementation Act – has languished in parliamentary committees since 2020; at time of writing, it has yet to pass its third reading in the lower house. The glaring absence of anything even remotely approximating “adequacy” with the GDPR under Canadian law poses a live and very real threat to our global trade in digital, and hence all other, services. Data regulators in the EU member-states (and elsewhere) are no doubt running thin on patience for our great national dawdle.

This sorry state of legislative affairs stands in stark contrast to the case of the Liberal government’s latest plan to shake down Big Tech firms and hand that cash out to their friends at our Big Three telcos and legacy media *ahem* “enhance fairness in the Canadian digital news marketplace and contribute to its sustainability”. Having been introduced as Bill C-18 in the House of Commons in April 2022, it progressed with such lightning pace (by legislative standards) that a mere fourteen months later, the Online News Act would receive Royal Assent on June 22, 2023.

The immediate and practical effect of that Act‘s passage – as has been plainly clear from the outset, to all parties involved, were the Government were to adopt it – has been the wholesale excision (for now) of all news content from Canadian sources from the search results and social media feeds of many Canadians. The Online News Act was, is, and by all indications shall remain a bewildering act of deliberate, state-level self-harm; a sudden, catastrophic stupefaction of the nation’s civic sphere. And we’ve still not gotten around to passing GDPR-like data protections, more than five years after such rights were extended to all residents of the European Union.

Day by each passing day, Canadians – and Manitobans in particular, as this province’s recent 24-hour “it’s not -a-cyberattack-oh-wait-oops-yes-it-was” news cycle perfectly exemplified – become further and further entrenched in a pitiable form of cyber-serfdom uniquely of our own design. We struggle to eke out our wretched digital existences, here at the outermost peripheries of the modern global information economy. This alone ought reasonably to be considered intolerable by many.

Now, add to these troubles the possibility that our Progressive Conservative government may have leveraged public monies and resources, in coordination with partisan third-party election advertisers, so as to advance that party’s own partisan messaging priorities by alternative means in the lead-up to a general election. And that the single, underlying, unifying objective of all these efforts would seemingly have been: frighten all the mums.

My only hesitation in characterising the Manitoba Government’s recent activities as “a state-sponsored domestic PSYOP” lies with how, as a matter of US military doctrine, “PSYOP forces will not target… citizens at any time, in any location globally, or under any circumstances”. They were a state-sponsored domestic psyop, though.

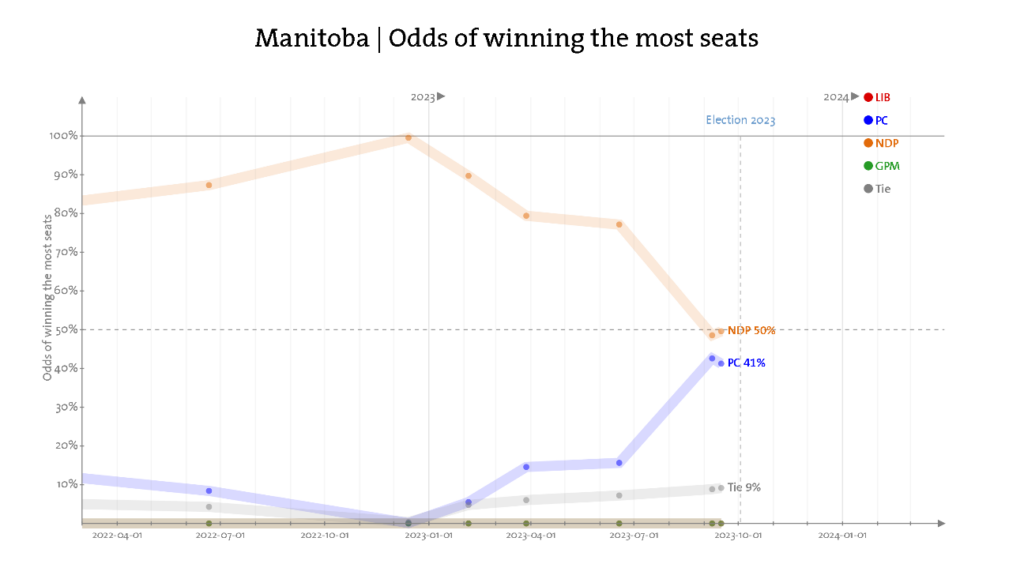

It need not always be so; we need not live always like this. All that is needed to avoid it is a common public will to reject such politics, and a common language with which its alternatives can be expressed. It is to be hoped that Wab Kinew, and his Manitoba NDP, can manage to find both. If they do not, then the election outcome in Manitoba largely relies, at this point, on the forces of inertia. And lemme tell ya, one party has got momentum in heaps right now:

The election’s on October 3rd; it’s a Tuesday. Don’t forget to vote, I’ll see you next time for Part III!

-R.