You are already familiar, I have no doubt, with the phrase “to boil a frog“.

According to the story — and you know this bit, too — if you plop a frog down into a pot full of boiling water, then that frog will simply hop right back out again. But if you were to instead place that same frog down gently into a pot full of tepid water, and then gradually bring it to a boil on the stove, then the frog will remain in the pot, oblivious to its rising mortal danger, until it has been cooked alive.

Literary and rhetorical critics have a proper term for stories like this. Apalogues are brief, pithy narratives meant to assert or express one’s moral (or other) argument, but in a pleasing and indirect manner. Indeed, the whole purpose of the thing is to get some given moral claim across, and so distortions and exaggerations commonly feature in such stories. Aesop’s Fables contain a multitude of examples, except nobody calls them “Aesop’s Apologues”. I can only assume this is the end result of some globe-spanning and centuries-long conspiracy to annoy me, and me specifically.

The “boiling frog” of the story is rubbish, of course; by now, people have tried dropping the frogs, and they have reported that when you drop a frog in boiling water, it normally just dies. And when you place one down gently in a pot of only tepid water… well, they hop out anyways. Frogs are like that, sometimes. Here in our shared reality, frogs are normally capable of thermoregulation, a trait they share (to some degree) with just about every known form of sentient life. But that isn’t really the point.

The point is that this myth of the “boiling frog” persists in our culture — in spite of all the howling pedants of the world — largely thanks to its rhetorical usefulness. The story is a warning against complacency, often invoked where the immediate and perceptible changes arising from some perceived threat may only be gradual or slight.

Whether or not this is actually the proper argument to be made in a given moment is another question – and largely, one of taste. Still, I was quite surprised to learn (after going through this blog’s archives to check) that I haven’t used the phrase myself, here, in the past. It feels like I bring that one up all the time.

Snaaake, a snake, oooh, it’s a snaaake…

Anyways. I have another famous apologue in mind, and wish to discuss it here. You may be less familiar with this one, but it seems destined to enter our shared public lexicon sooner rather than later. Horst Siebert, the eminent German economist, is widely credited with having first popularised it through his 2001 book, “Der Kobra-Effekt“. Siebert uses this phrase, and the attending apologue, to illustrate a concept that economists have their own proper term for: “perverse incentive“. Simply put, this is when you set up some reward structure/system (or incentive), in order to accomplish some goal, but instead you wind up even further away from your target, or else you inadvertently make some other problem worse. Examples of “perverse incentives” abound in the real world — as do the many varied “cobra effects” that these can produce.

The story behind “cobra effects” goes something like this: in the days of the British Raj, the colonial government in India became concerned with the number of deadly, venomous cobras on the streets of Delhi. So, the British governors made an offer to the people of Delhi: for each dead cobra you bring to us, we will pay a bounty. And for a while, this policy seems to work out just as intended; many cobras are collected, and the British pay out even more in bounties than they had initially planned. Some begin to feel as though they see fewer cobras on the streets. And yet… well, there are still cobras on the streets. Soon, rumours begin to spread about some enterprising folks who have taken up snake-breeding, raising cobras in captivity just to kill for the bounties. When these rumours reach the British governors, they elect to scrap their cobra-bounty altogether. And when the bounty policy is scrapped, the snake-breeders — who, for the purposes of this story, were actually real — simply free the now-worthless snakes they had been raising. As a consequence, the local cobra population explodes, and the problem of deadly snakes in the streets of Delhi is made worse than ever.

As far as digestible moral anecdotes go, this one is… fine. It’s fine. But as an apologue for the harms which can be wrought by a perverse incentive, “cobra effects” is — this is just my opinion, and with all due respect — lousy. It is not lousy simply (or rather, only) because the anecdote that I just relayed is a more-or-less total fabrication, which has been thoroughly and repeatedly debunked (most recently, and perhaps most thoroughly, by the Friends of Snakes Society). Much like the fabled boiling frog, “cobra effects” might have proven too useful to lose — troubling colonial overtones and all — if the narrative expressed its more fundamental argument suasively. No, it is lousy as an apologue because it does not.

The problem (to my mind) is that within the context of systems thinking, this narrative might lead one to conclude (sensibly, even) that the snake-breeders are to blame for all these new cobras on the streets — the “cobra effects” — whereas the point, the vital point is that it was the British governors who were at fault, because they introduced the “perverse incentive” in the form of a cobra-bounty. Invariably, “cobra effects” stem from some regulatory failure, and “regulating things” is the jealously guarded purview of leadership; of management. The purpose of a system is what it does.

I believe that is the point, at least. I would argue this more strongly if I could, but sadly, no official English translation of Der Kobra-Effekt has yet been published (and I am ill-equipped to understand three hundred pages of German). Further complicating matters is the fact of Herr Siebert’s death in 2009… so we can expect no further comment from him on the subject.

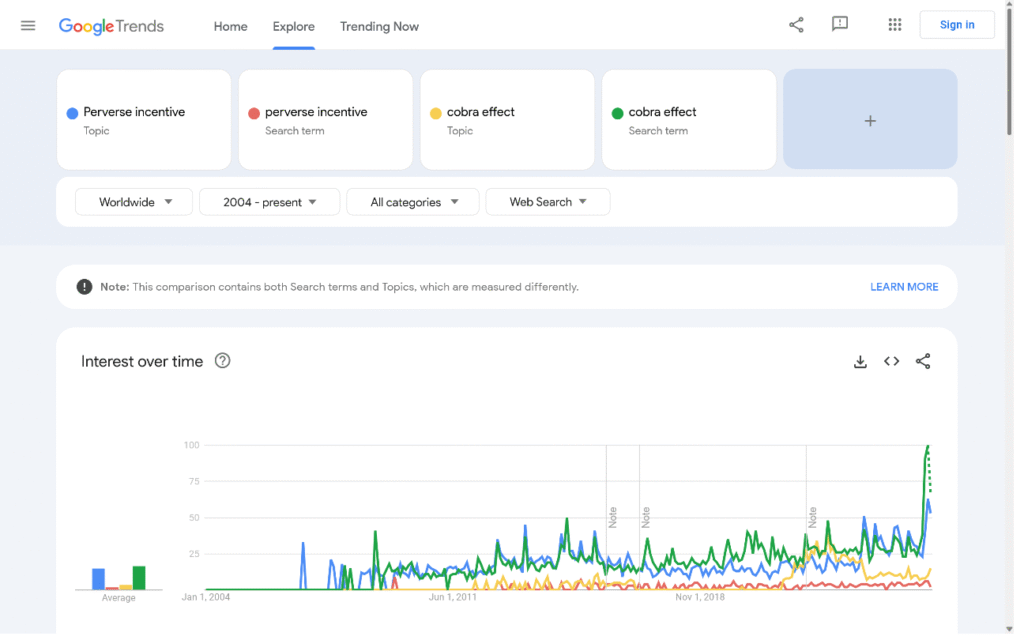

Be that as it may, Siebert’s “cobra effects” have by this time slithered their way out of economist circles, and into the broader public vernacular. If Google Trends reports are anything to go by, there seems to be a growing global interest in “perverse incentives” in general, and “cobra effects” seem to have become the prevailing mental shorthand for the unintended harms they can bring about.

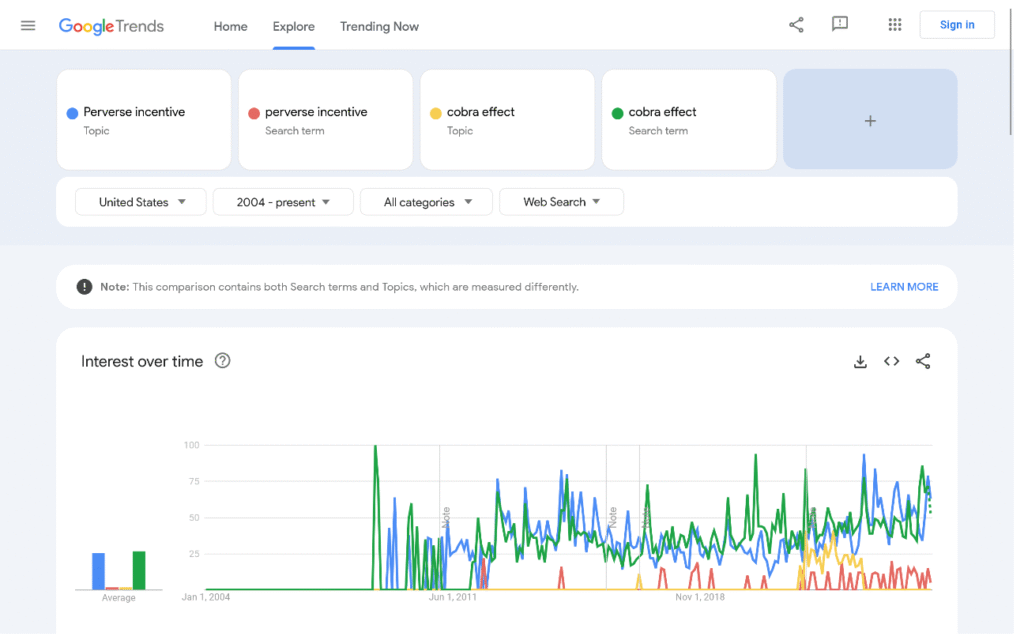

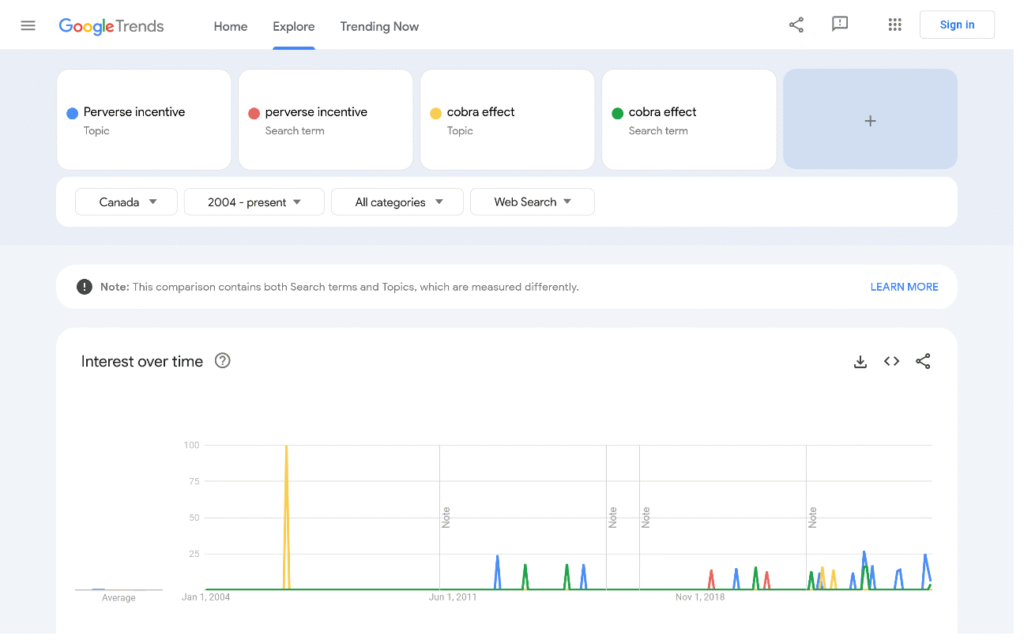

These same Google Trends reports suggest that there is relatively low search interest in these terms and topics amongst Canadian users, compared to those in similar nations. It is as if this were some rhetorical blind-spot in the collective “Canadian” mind. Either that, or my information is bad. Here it is, or was:

Google Trends, Worldwide, 2004–2025

Google Trends, United States, 2004–2025

Google Trends, Canada, 2004–2025

Thankfully, pop culture has afforded us with its own case-studies in perverse incentive. I am thinking of the so-called “Streisand effect“, wherein an attempt to suppress or censor information leads it to greater publicity and exposure. There is a rather fascinating research paper, published in Marketing Science earlier this year, which suggests that a book subject to organised “book bans” at the local or even state level in the United States sees a twelve per cent bump, on average, in its circulation. In seeking to limit and proscribe certain speech, “book bans” instead have the general tendency of amplifying it. The obvious conclusion to be drawn is that “book bans” are great for book sales, and any jobbing writer should, under these circumstances, actively court organised efforts to have their speech proscribed. Willies willies cocks, trans rights cocks climate change.

Or consider the example from just this past week, where an ad campaign appearing on U.S. network television – paid for by the Government of Ontario, at a reported cost of ~$54 million USD, to express opposition to Donald Trump’s tariff policies — has apparently so enraged the Usonian President that he now thunders for all trade talks with Canada (his state’s second-largest national trading partner) to be “HEREBY TERMINATED“. All the while, he donates tens of millions of dollars worth of free attention — among we marketing pricks, the proper term is “earned media” — to the provincial Government’s campaign and its message, which now garners both national and international headlines (plus think-pieces, detailed explainer guides, etc.). With each fresh late-night social media temper-tantrum that he throws, President Trump draws an ever larger gaze towards this (apparently, quite impactful) line of critique. Analogies to the biblical Goliath, and David with his sling, are not unwarranted.

But the point I was after is this: it seems likely that we can expect to encounter many more novel species of “cobra effects” in the days ahead, especially insofar as Usonian politics are concerned. “Perverse incentive” is, and has been, the polite and proper term for describing a lot of what is currently happening, and why it’s all likely to end in tears, someday soon enough. I am suggesting that the global public (and Canadians in particular) will have need for some shared, common language to discuss these. I am also suggesting that it would be preferable if this shared vocabulary didn’t reinforce outmoded colonial stereotypes, or lead us towards false conclusions as to the nature of our problems, or both.

In that spirit, I would like to propose the term “pigtails” (or “pigtail effects”, if you like) as a direct, swap-in, find-and-replace-all alternative for “cobra effects”. My first rationale is the story behind my preferred term — the apologue — which I will relate in a moment. It’s a similar story to the one behind “cobra effects”, with certain key distinctions, and it even has the added persuasive benefit of being mainly true. My second rationale is mnemonic: the first two letters of “pigtail” (in English, at least) are the same as the initials for Perverse Incentive. My third rationale is the corollary observation that if one should ever seek to find the “root” of a pigtail, one should not be surprised if they discover, once they get to the bottom of things, that there was always just some random arsehole behind it. Ahem:

Hogging the attention

Wild pigs are an invasive species in North America, and the ways they live and forage can be acutely destructive to their environs. They root up the forests. They root up the fields. They can even root up the streets, if they put their minds to it. And for a period of about sixty years, soldiers on a U.S. Army base named Fort Benning (on the Georgia side of the Georgia-Alabama border) had been reporting problems with the pigs who roam about the place. By the late 2000s, it was estimated that about six thousand wild pigs lived on the grounds of the base.

And so, the U.S. Army assigned an officer — one Maj. Bobby Toon — to sort this porcine problem out. Somebody dubbed him the “Pig Czar” of Fort Benning, and the nickname stuck. At first, the Major called in some contractors; civilians. “We want to get rid of the pigs”, he told them. And after a little while, some of the contractors replied. “We can do it,” they told him, “here is what it would cost.”

But the Major — an avid sport hunter himself — felt that the prices he was quoted were too high, or that the contractors were simply being greedy. Besides, he thought, there were two thousand other hunters who already had licenses to hunt on the grounds of the base. That’s just three pigs for every licensed hunter. And so, in June 2007, a new bounty program was announced: for every pig tail turned in at Fort Benning, the United States Army would pay out a bounty of forty dollars.

Over the next nine months (June 2007–February 2008), about eleven hundred bounties were paid — that is, wild pigs were killed — at a total cost of about $57,000USD, of which bounties made up roughly $45,000. And yet, over that same timeframe, a population study on the wild sounders in two areas of the base would find that the hogs were healthier and more numerous than ever. The pigs of Fort Benning were positively thriving!

Now, at about this time (or perhaps earlier), rumours began to swirl about some “bounty hunters” who were going around to local meat processors, buying up pig tails from these sources, and then turning these in for the bounties. There might even have been a kernel of truth to those rumours… but even this would not explain why the pigs living on the base were faring quite as well as they were now. What was going on?

Nearly ten full years went by before the population study was published, and the researchers could share their own hypothesis. They believed that it was the local hunters’ practice of “feed-baiting” wild hogs which created the more abundant food supply, and thus greater reproduction, than might otherwise have occurred. The researchers also observed that many local hunters would prioritise the killing of larger, older male “trophy” hogs, rather than females or juveniles, even where the per-tail bounties were identical. As the civilian contractors might have told the good Major, culling mature males alone does not especially threaten the survival of a sounder. The rest can usually manage just fine.

In any event, the U.S. Army would opt to keep its pig-tail bounty at Fort Benning for at least a few more seasons. Today, wild pigs still roam free in and around the base. But Major Toon did get to bring Gordon Ramsay out on a hunting trip once (plus his video production crew), so that was something.

Getting back into my lane

In closing — and in order to maintain the thin veneer of this still being a professional blog — it behooves me to return to the subject of digital marketing. Let us discuss one last “perverse incentive” that I encounter all the time in my own working life.

Somebody out there wants to advertise; this is the principal, who often hires an agent, and so the two parties have an agency problem on their hands. What is the incentive structure? Well, for simplicity’s sake, it is often arranged such that the agency shall be paid a fixed percentage of the “ad buy”, or direct media spend, to administer the campaign. That is simple enough.

But can you imagine — would you believe? — that the advice of such an agency will often boil down to “… and that’s why we should raise the media budget”? Or that an agency under such a fee structure rarely, if ever, recommends that the spend be reduced? Even when the agent sees clear, obvious signals that this is the most impactful “optimisation” to be feasibly made?

No wonder, then, that the average advertiser’s media spend tends to creep ever-upwards, just as the profits of Alphabet and Meta — a functional duopoly in this space — continue their unabated rise. In recent years, some online marketers have (belatedly) rediscovered the idea of incrementality… but you will never hear the word uttered by any agency that works on a fixed percentage of ad-spend, unless they absolutely have to.

Or suppose that some other advertiser offers to pay their agent for some fixed number of hours per week, so long as their ad campaigns are in-flight, to manage them. Whether the scope of time and effort involved is well-suited to the task at hand hardly even enters into it. But would you believe me if I told you that under this incentive structure, “Parkinson’s law” tends to rear its head, and the work tends to expand to fill whatever time is granted for it? Small wonder, then, if the “management” of such campaigns should tend towards the delivery of “minimum viable products”, combined with some form of corporate theatre, technical make-work which borders on alchemy — and with much the same result.

Pigtails are everywhere, once you know what to look for. Perhaps you’ll find a few of your own, out there in the wilds. Happy Hunting,

-R.